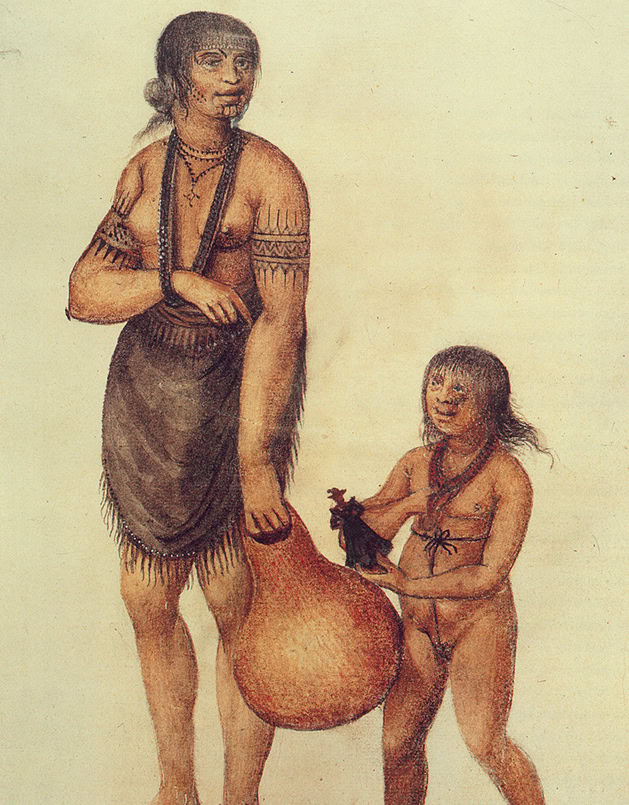

Algonquin Native Americans

The Carolina Algonquian had been living on the Outer Banks long before the first English expedition arrived in 1584. Archeological evidence suggests that native peoples arrived in North Carolina around 9500 to 8000 B.C., with the first evidence of Outer Banks habitation occuring between 2500 to 2000 B.C. By the time the first English expedition arrived at Roanoke Island in the summer of 1584, the Algonquian had inhabited the region for at least 800 years. Their culture was rich and varied, and their methods of self-sustainment were of immediate fascination to the arriving English.

Information from the National Park Service.

The arriving English were immediately impressed with the fishing techniques the Algonquian had honed over centuries. The Algonquian used weirs, a type of underwater netted fencing, to effectively corral native fishes (flounder, trout, mullet, etc.). In addition, they employed sharpened wooden poles for a type of spearfishing. Lacking modern-era fishing rods and lures, the Algonquian fishing methods were nonetheless effective. As Thomas Hariot wrote of Algonquian fishing methods: “The inhabitants take them in two manner of ways, the one is by a kind of weir made of reeds…The other way, which is more strange, is with poles made sharp at one end, by shooting them into the fish…either as they are rowing in their boats, or else as they are wading in the shallows.”

For hunting land-based game, the Algonquian primarily used the bow and arrow. As Hariot also observed about hunting black bear: “The inhabitants in time of winter do use to take and eat many. They are commonly taken in this sort in some islands or places where they are, being hunted for as soon as they have spial of man, they presently run away, and then being chased, they climb and get up in the next tree they can. From whence with arrows they are shot down stark dead, or with those wounds that they may after easily be killed.” In addition to hunting black bear, the Algonquian also relied on deer as a food and hide source.

Fish and wild game were not the only source of food for the native population. In addition to gathering fruits and nuts, the Algonquian practiced farming. Corn, or maize, was common, as were different types of beans, pumpkin, and squash.

Tobacco, called Uppowoc, served a variety of purposes for the Algonquian, including religious ceremonies and medicine. As we know, the English quickly took a liking to the Algonquian-cultivated tobacco and it became an exotic crop that was immediately desired in Europe. Thomas Hariot remarked on the importance of tobacco to the Algonquian: “This Uppowoc is of precious estimation amongst them, that they think their gods are marvelously delighted therewith…”

Algonquian religious beliefs were recorded extensively by Thomas Hariot. Although his perception of their religion was biased (he believed they should be converted to Christianity), he nonetheless is able to give us a good description of their beliefs and practices.

As Hariot wrote, the Algonquian believed there was “only one chief and great god, which has been from all eternity.” However, this one god created many lesser gods “to be used in the creation and government to follow.” These lesser gods created the sun, moon, and stars first, followed by water. Woman was created next, followed by man.

All Algonquian gods were represented by “images in the form of men, which they call Kewasowok…Then they place in houses appropriate or temples, which they call Machicomuck, where they worship, pray, sing, and make many times offering unto them.”

When the English arrived on the Outer Banks in the 1580s, they were quick to discover that the Algonquian culture was highly sophisticated. Estimates of the Algonquian population along the Outer Banks during this time were between 5,000 and 10,000 people spread throughout multiple subcultures and town centers. John White’s and Thomas Hariot’s documentation of these town centers proved invaluable to European understanding of the New World.

John White in 1585 made detailed drawings of two of these towns, Pomeiooc in present-day Hyde County and Secoton in present-day Beaufort County. In addition to White’s drawings, Thomas Hariot described the structures in these towns in detail: “They were made of small poles made fast at the tops in round form after the manner as is used in many arbories in our gardens of England…In most towns, the houses were covered with barks, and in some with mats of long rushes, from the tops of the houses down to the ground.”

The native population traveled from town to town, conducting business, trading, participating in religious and political activities, warring with other tribal groups, and sharing the same (now virtually extinct) Algonquian language. The English historical record indicates that there were at least ten Algonquian towns located in the Outer Banks region in the late 1500s.

The second English expedition to the Outer Banks in 1585 permanently altered the Algonquian presence in the region. The 115-man English military detachment brought disease with them that the Algonquian had little to no immunity to (likely smallpox, influenza, and even the common cold). Within months many native peoples had succumbed. This in turn created hostility toward the English and a series of conflicts occured as a result, permanently shattering the once-promising, yet tenuous, Algonquian/English relationship.

By the time the English began to permanently settle eastern North Carolina in the late 1600s the vast majority of the Algonquian population had perished or left the region.

Manteo

Manteo, a Croatoan member of the Carolina Algonquian, traveled to England with Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe, the two leaders of England’s expeditionary mission to the Outer Banks in 1584. Manteo’s arrival in England was likely treated with great curiosity; the vast majority of Europe had never seen a Native American before.

Upon arrival in England, Manteo was taught english by Thomas Hariot; Hariot in turn learned the fundamentals of Carolina Algonquian from Manteo, enough to begin development of a rudimentary Algonquian alphabet. By the end of 1584 Manteo had learned English well enough to act as an interpreter for the English, going so far as to describe the Algonquian social structure and cultural traditions. In addition, Manteo served an important purpose for the development of an English colony; his presence attracted investors to the New World.

Manteo returned to Roanoke with the second English voyage of 1585, remaining loyal to the colonists throughout. He disappeared from the historical record in 1587, along with the Lost Colony.

Wanchese

Wanchese, a Roanoac member of the Carolina Algonquian, traveled with Manteo to England in 1585. Like Manteo, his arrival was met with great curiosity by the English.

Along with Manteo, Wanchese learned english from Thomas Hariot and taught Hariot the fundamentals of the Algonquian language. Both served as interpreters, providing the English with an understanding of Algonquian culture.

Upon returning to Roanoke in 1585 with the second English expedition, the paths of Manteo and Wanchese differed greatly. Whereas Manteo remained loyal to the English, Wanchese became very distrustful. He encouraged his fellow Algonquians to avoid interactions with the English and attempted, often through violence, to put a halt to further English expansion in the region.

Wanchese, like Manteo, disappeared from the historical record in 1587.

Wingina

The chief of the Native American tribes in the area, Wingina was not present when the English first landed but was well enough to open peaceful negotiations through his brother, Granganimeo.

Inviting the English to settle on settle on Roanoke Island, Wingina soon regretted his decision as disease and starvation ravaged his tribe. Changing his name to Pemisapan, this chief began to plan the destruction of Ralph Lane’s colony on the island. Unfortunately his plan was betrayed and Lane attacked his nearby village, killing Wingina/Pemisapan and many of his people.

Granganimeo

Acting in his brother’s stead (Wingina was recovering from battle wounds), Granganimeo at once realized the power that the English wielded when they first arrived in 1584. Mostly through hand gestures, he made the English comfortable, traded with them, and invited them to return the next year.

Unfortunately, he would not survive the ravaging diseases that his new English allies would bring and died in the spring of 1586.