The Lost Colony

Experience The Lost Colony

The Lost Colony, now in it’s 88th Anniversary Season, is one of the most exciting nights of theatre on the East Coast. An Outer Banks tradition recently updated to appeal to modern audiences, The Lost Colony is an important part of any summer trip to the beach.

History Comes Alive. The Lost Colony tells the true story of the first attempt at English colonization in America and the Colony’s encounters with the Algonquin Native Americans who lived there. In 1587, 117 men, women, and children set sail from Devon, England to establish a permanent colony in the New World and eventually landed on Roanoke Island. Shortly after arriving, the leader of the Colony, Governor John White, returned to England to gather more supplies. War with Spain delayed his return to Roanoke Island for three years, and when he eventually made it back to the Island he found that the Colony had vanished, leaving only the letters “CRO” carved into a tree. Where did the Colony go? Thus one of history’s most endearing mysteries was born.

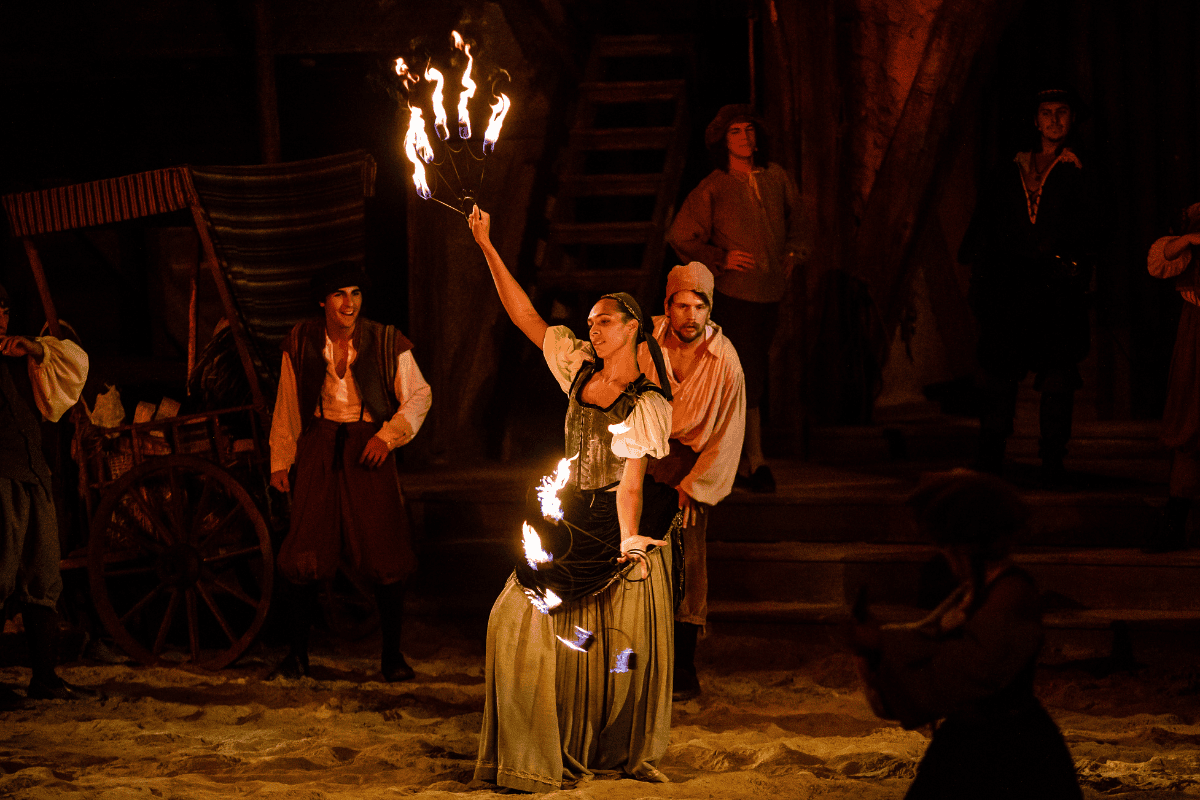

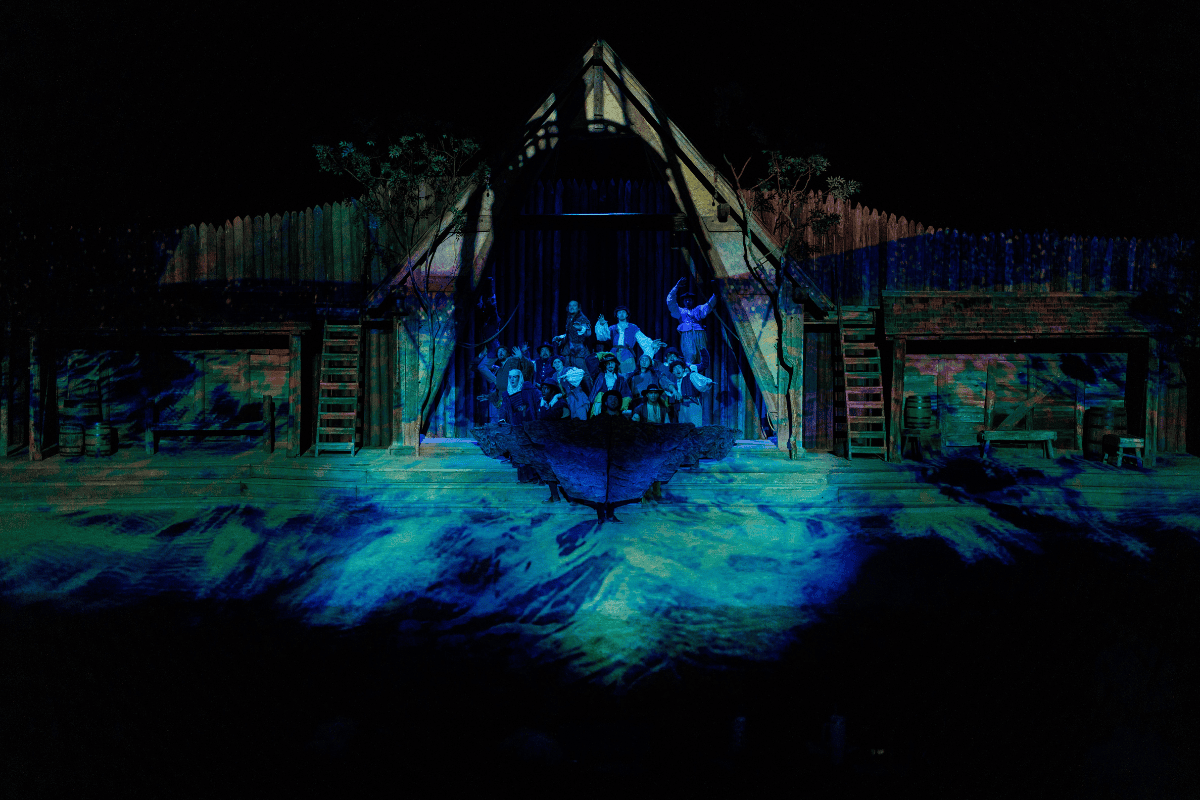

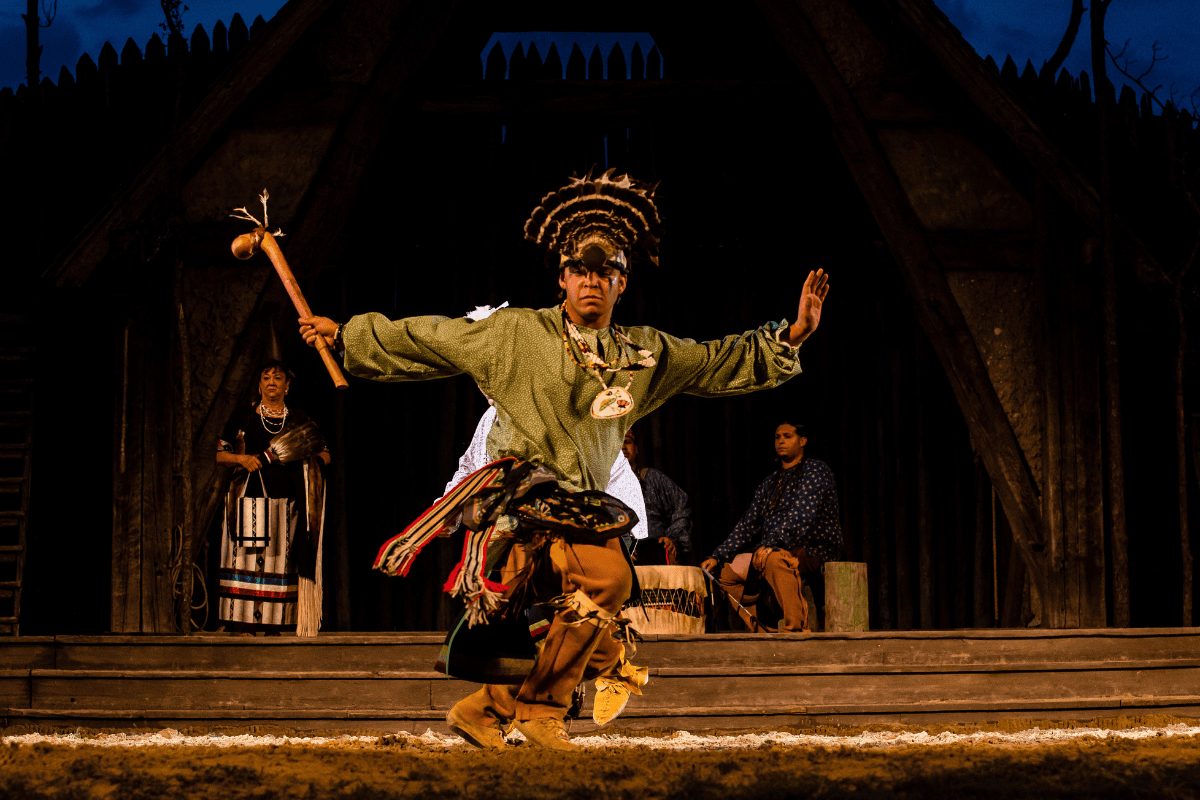

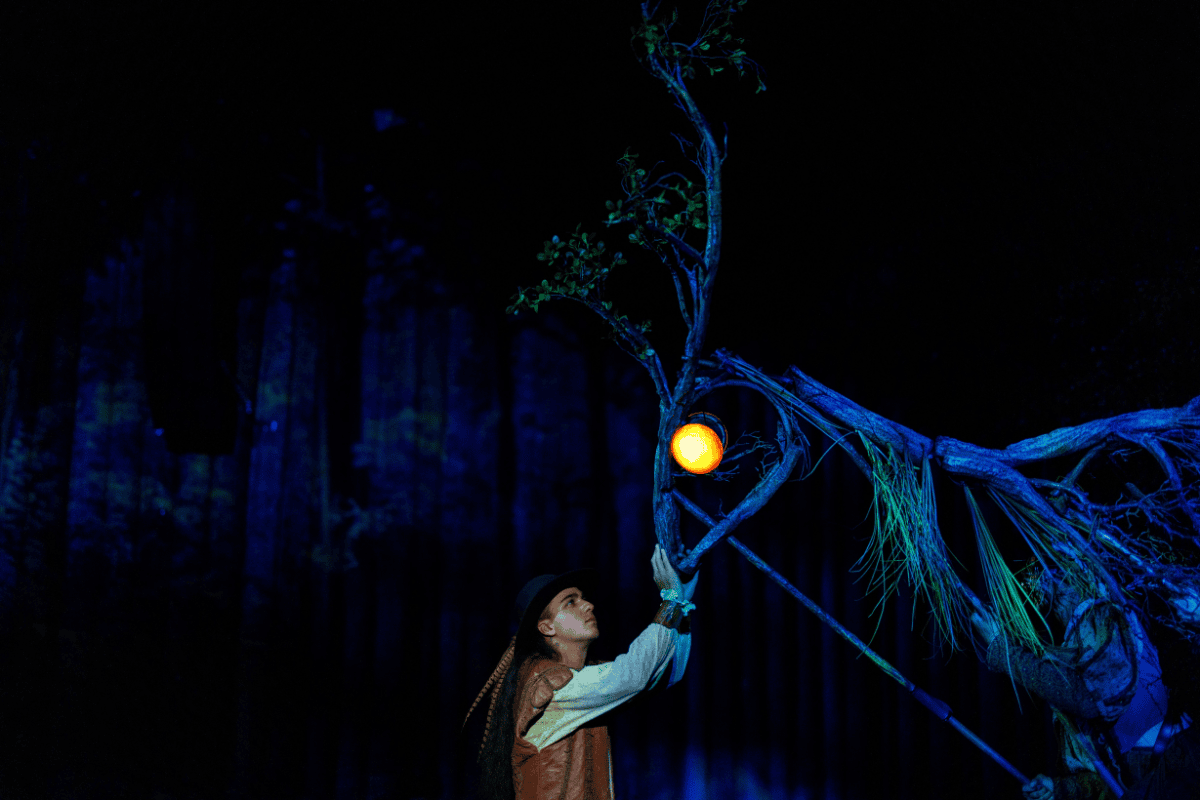

Fun For The Whole Family. Featuring spectacular dances, fantastical puppetry, breathtaking costumes, harrowing fights, jaw-dropping special effects, and a timeless story, The Lost Colony has something for everyone in the family. Theatre lovers, history enthusiasts and everyone in between will leave The Lost Colony trying to solve the mystery.

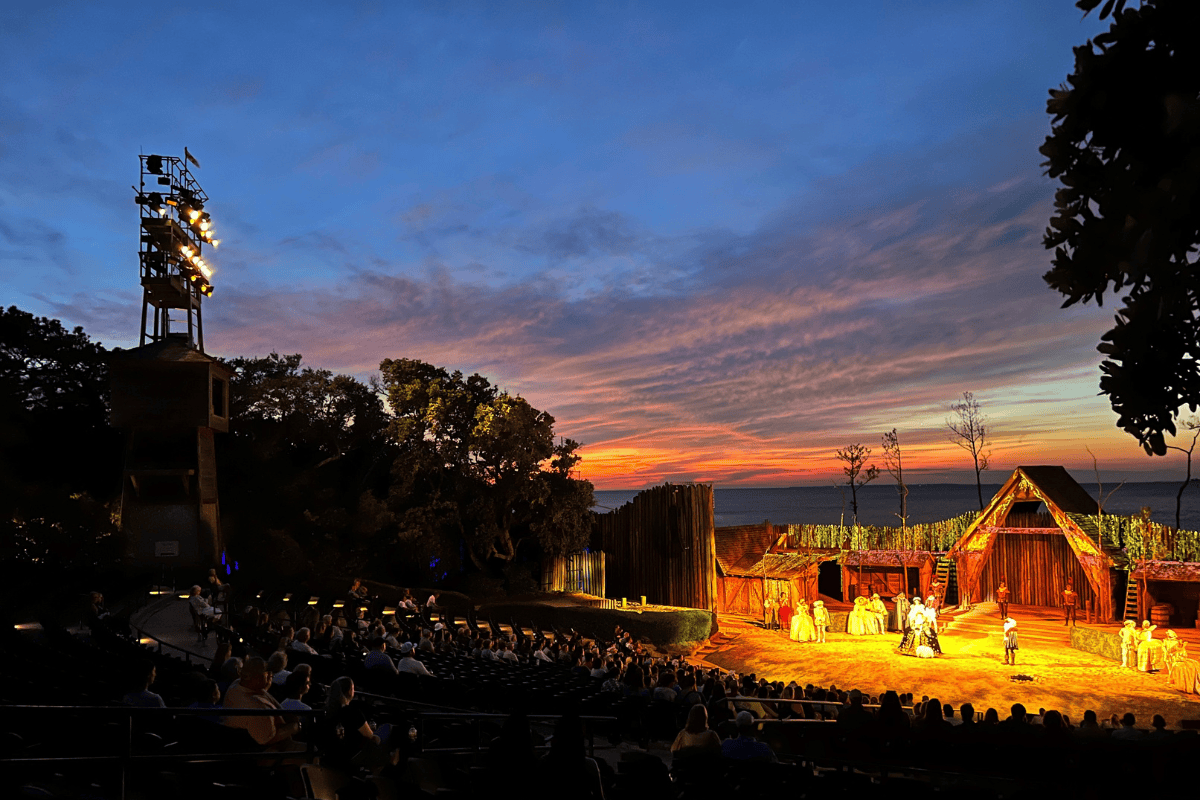

A Breathtaking Venue. The Waterside Theatre, home to The Lost Colony, is one of the most beautiful venues in all of live entertainment. Located within Fort Raleigh National Historic Site and nestled along the shore of the Roanoke Sound, The Waterside Theatre is home of one of the best views of the sunset on the Outer Banks. After the sunset, make sure to look up and witness the clearest sky and some of the brightest stars on the East Coast. The Waterside Theatre also offers a concession stand, bar, and gift shop.

More Than Just a Show. Make sure to come early to hop on a Backstage Tour and learn more about all that goes into putting on the massive production that is The Lost Colony. On Tuesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays, come early for the free Native Pre-Show, an educational and entertaining look at different styles of Native American dances performed by the Native American Company of The Lost Colony.

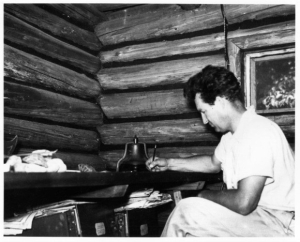

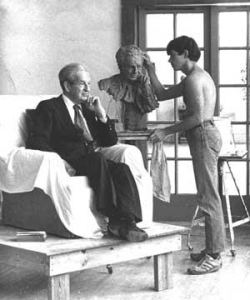

Author Paul Green

From childhood, his deep convictions about the immoralities of racial discrimination, capital punishment and military conflict colored everything Paul Green did and wrote. In addition to receiving the 1927 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for his Broadway play In Abraham’s Bosom – remarkable for its time in its serious depiction of the plight of the American Negro in the South – Green formulated and propagated a new dramatic form, the symphonic drama, a particular form of historical play, usually set on the very site depicted in the action, and embodying music, dance, pantomime and poetic dialogue. The first of these was The Lost Colony. He wrote sixteen more. It has been said that America has contributed two important new dramatic forms, one being the musical and the other being the symphonic drama, of which over 50 are in production around the country.

Paul Green’s total literary output included not only symphonic dramas, but other plays of various types, essays, books of North Carolina folklore, several novels, and a number of cinema scripts for such prominent stars of the 1930s as Will Rogers, Bette Davis, Janet Gaynor, among others. One of his Broadway plays, an early precursor of his symphonic drama form, was the 1936 anti-war play Johnny Johnson, whose music by Kurt Weill was Weill’s first American effort after his arrival from Nazi Germany. In 1941 Green worked with Richard Wright in adapting Wright’s celebrated novel Native Son to the Broadway Stage.

Paul Green grew up on a cotton farm in rural Harnett County, N.C., learning the value of hard physical labor as well as the importance and beauty of literature and music. He read books in the fields as he followed a mule-drawn plow and taught himself to play the violin; he would later compose music for his own dramas. After graduation from Buies Creek Academy, Green taught school and played semi-professional baseball until he could earn enough money to go the University of North Carolina, but his college education was interrupted by World War I. After he returned to the University, he was a key figure in the early days of the Carolina Playmakers. Among his Playmaker friends was author Thomas Wolfe, and Green’s future wife, Elizabeth Lay. Green taught philosophy and drama at Chapel Hill until 1944, when he retired to devote his time to writing. In addition to his early Pulitzer Prize, his awards include two Guggenheim Fellowships, the National Theatre Conference Award, and nine honorary degrees. He was posthumously inducted into the Theatre Hall of Fame in New York in 1993, and the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame in 1996.

All his life Green was active in the cultural life of North Carolina, being one of the founders of the North Carolina Symphony and the Institute of Outdoor Drama, which serves the large nationwide community of symphonic dramas that sprung up after the model of Green’s original The Lost Colony. His relentless battle against the death penalty has found its successors in a number of organizations active in this field in North Carolina. He traveled around the world on behalf of UNESCO lecturing about the drama and about human rights.

A year after Green’s death, his colleagues and family formed the Paul Green Foundation, whose purpose is to foster his principles in the areas of creative writing, human rights and international amity by means of a series of grants and awards.

Paul Green’s historical significance stems not only from his influence on the art of the drama, which he loved so well and long, but from his influence on the social values of the South during a period when he stood almost alone in preaching the equality of the races, the richness of Southern tradition as possible source of great literature, and the perfectibility of every person, even the condemned felon.

The Roanoke Colony Memorial Association of Manteo

& Paul Green’s The Lost Colony

“In for a penny; In for a pound.”

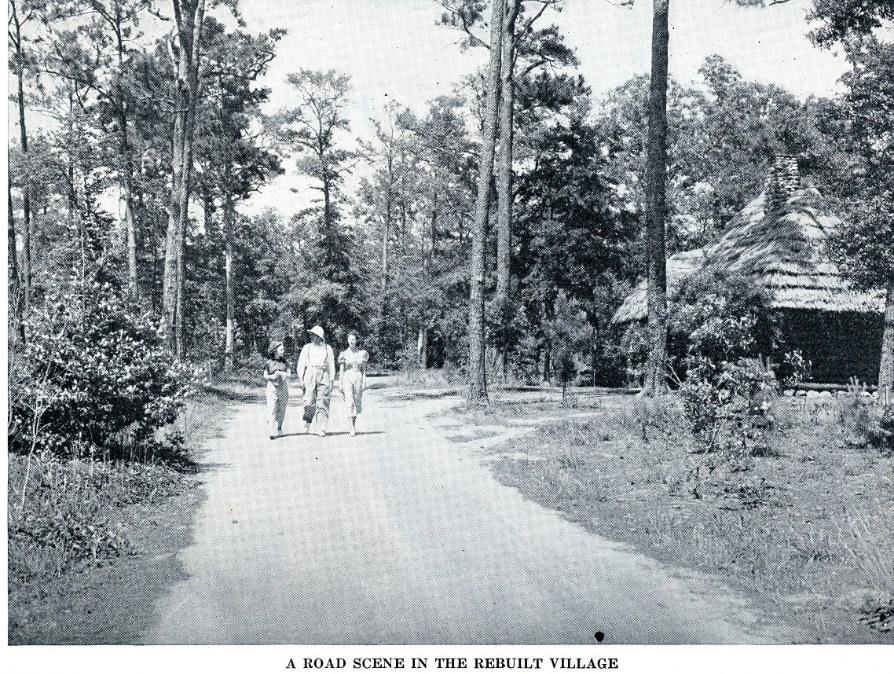

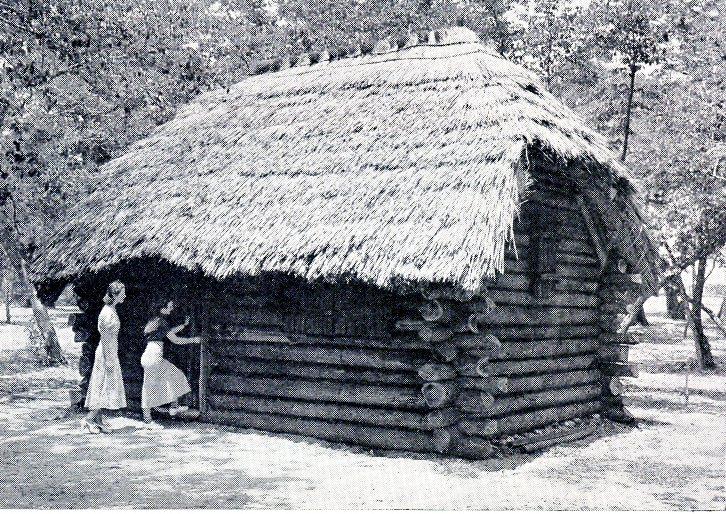

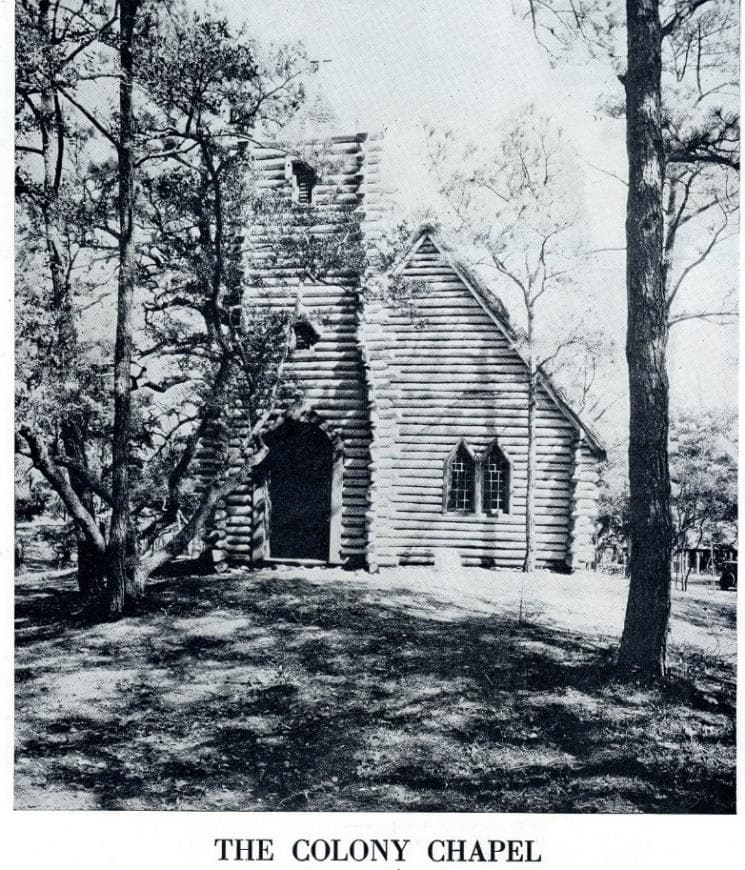

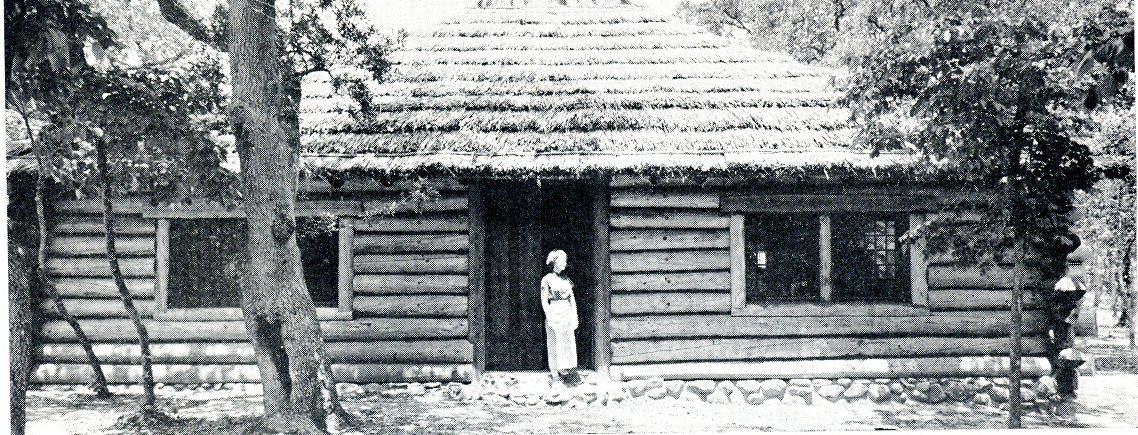

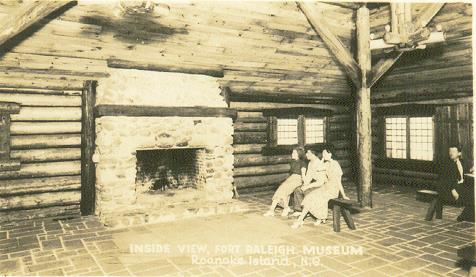

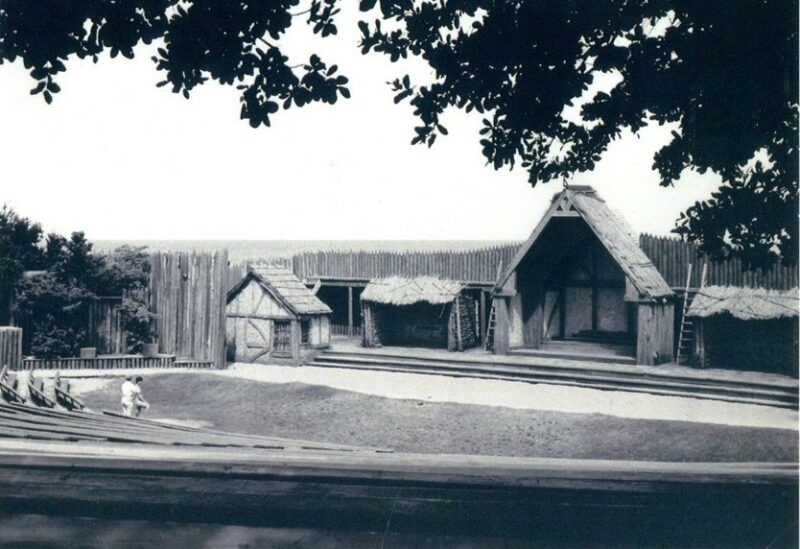

On 17 January 1937, the Roanoke Island Historical Association [RIHA] held a meeting in Manteo. They were aware their decisions would most likely determine their fate. Chartered in 1932, the group had boldly developed a 5-step plan to develop heritage tourism on Roanoke Island, the OBX and northeastern North Carolina. Even though the depression was raging throughout the country and other parts of the world, the group had met with success. On Roanoke Island, in 1934, the historic zone at ‘Old Fort Raleigh’, owned by the state of North Carolina, had been turned into a state park—a palisaded ‘lost colony’ village with log-structured palisade, guard houses, church, houses, and a refreshment/information structure. A Museum was in the works. Historians raged in the press about the anachronistic log structures—but tourism on Roanoke Island steadily increased.

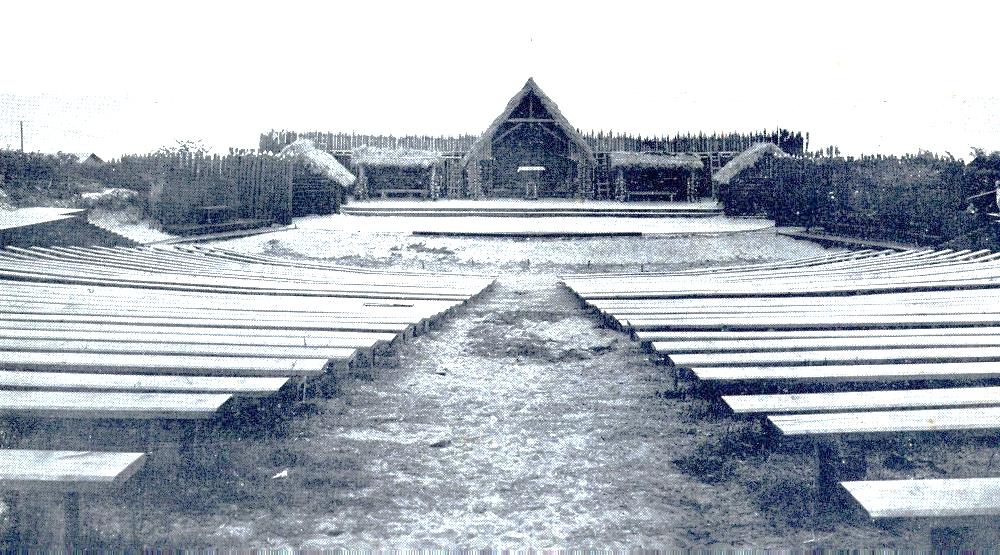

For 1937, the RIHA had scheduled a 3-day celebration on the 350th Anniversary of the birth of Virginia Dare on Roanoke Island on 18 August 1587. The event was to include the premiere of Paul Green’s yet unwritten outdoor drama, The Lost Colony, in the new, to-be-constructed Waterside Theatre at Fort Raleigh.

RIHA Chairman W.O. Saunders and his board members had agreed at the outset of the organization, that they would seek state and federal funding through the establishment of both a state and federal Roanoke Island Commission which would help start and sustain agreed upon projects. The RIHA would neither solicit funds from other sources nor depend on ticket sales for underwriting. The bill for creating the federal Roanoke Island Commission was well on the way to success—until funding was needed for depression relief and their bill was withdrawn. The RIHA was out of time. They canceled the celebration and the theatre production.

RIHA Chairman W.O. Saunders and his board members had agreed at the outset of the organization, that they would seek state and federal funding through the establishment of both a state and federal Roanoke Island Commission which would help start and sustain agreed upon projects. The RIHA would neither solicit funds from other sources nor depend on ticket sales for underwriting. The bill for creating the federal Roanoke Island Commission was well on the way to success—until funding was needed for depression relief and their bill was withdrawn. The RIHA was out of time. They canceled the celebration and the theatre production.

In late 1936, in anticipation of the RIHA decision, Bradford Fearing with several other Board members and friends, and with the knowledge of the RIHA board, formed the Roanoke Colony Memorial Association of Manteo [RCMA of Manteo], the primary purpose of which was to produce the 350th Anniversary of the Birth of Virginia Dare with a three-day celebration—which included the premiere season of Paul Green’s The Lost Colony outdoor drama.

In late 1936, in anticipation of the RIHA decision, Bradford Fearing with several other Board members and friends, and with the knowledge of the RIHA board, formed the Roanoke Colony Memorial Association of Manteo [RCMA of Manteo], the primary purpose of which was to produce the 350th Anniversary of the Birth of Virginia Dare with a three-day celebration—which included the premiere season of Paul Green’s The Lost Colony outdoor drama.

On 18 January 1937, Bradford Fearing—representing the RCMA of Manteo—contracted Paul Green to write a pageant-drama about Sir Walter Ralegh’s fabled lost colony of Roanoke. Opening night was set for 8:15pm, 4 July 1937 and a second performance the Monday night following; then through Labor Day with performances on Fridays, Saturdays & Sundays; plus eight additional performances on other evenings. There was no theatre, no script, no music, no choreography, no lights, no sound, no costumes, no props or sets, no singers, dancers, actors, technicians, nor house staff—and of course, there was very little money and time was short, just a little over five months until opening night.

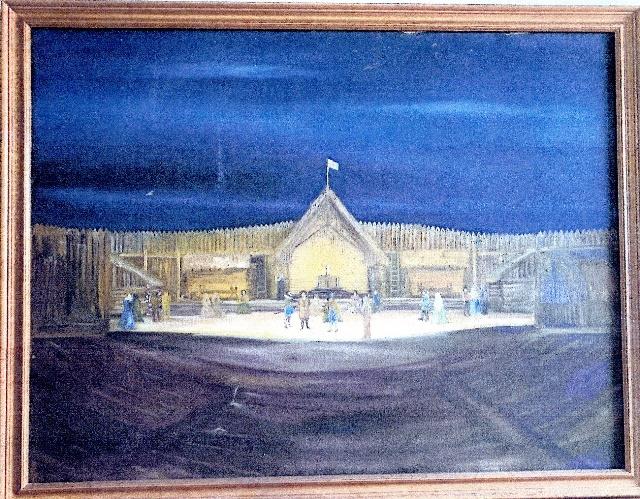

Using the Dare County Courthouse—where most of the RCMA of Manteo members and directors were otherwise employed—as the organization’s administrative office, the group breathed new life into the celebration plans. Bradford Fearing knew that A.Q. ‘Skipper’ Bell, who had been Construction Supervisor for the Cittie of Ralegh State Park could get the theatre built, even knew what it would look like because Bradford Fearing had seen the large picture Skipper had painted after several conversations with Paul Green and the directors;

Using the Dare County Courthouse—where most of the RCMA of Manteo members and directors were otherwise employed—as the organization’s administrative office, the group breathed new life into the celebration plans. Bradford Fearing knew that A.Q. ‘Skipper’ Bell, who had been Construction Supervisor for the Cittie of Ralegh State Park could get the theatre built, even knew what it would look like because Bradford Fearing had seen the large picture Skipper had painted after several conversations with Paul Green and the directors;

Bradford Fearing knew that Paul Green could write the play, assemble the necessary artistic teams and performers; knew that Mabel Evans would organize auditions for local performers; knew that the local people could provide necessary housing for off-island performers; knew that W.O Saunders, Josephus Daniels, Ben Dixon MacNeill and Victor Meekins could launch local, state and nationwide newspaper and radio campaigns; knew that R. Bruce Etheridge of the NC Department of Conservation and Development would spearhead publicity within the state; and Bradford Fearing knew that the Dare County Chamber of Commerce could organize and produce side events to enhance the celebration.

Bradford Fearing knew all that, but he also knew that the project needed money, a lot of it, and Bradford Fearing knew that Congressman Lindsay Warren would facilitate funding through the Works Progress Administration, Civilian Concentration Corp and the Federal Theatre Project, and Bradford Fearing knew that his own contacts in the NC General Assembly and state government agencies would help through state relief programs, and Bradford Fearing knew that members of the Manteo business community would provide no-interest loans if necessary. But ready cash ceased to be a problem after Congressman Lindsay Warren’s bill passed the house & senate and the US Mint issued 25,000 commemorative Roanoke Island half-dollar coins to the RCMA of Manteo. Bradford Fearing sold half of them to a collector in Texas to re-coup the cost of minting the lot and used the other half to sell to the public, to use as collateral for bank loans, and on occasion, to pay local performers in the production.

Bradford Fearing was right; it all happened: the theatre was constructed and equipped, the play was written, cast and rehearsed. Sets, costumes and props were constructed and lights installed and cued. Publicity had exceeded everyone’s expectations. Programs, playbills and tickets were printed, and the box office and house staff were ready to greet theatre patrons.

On 4 July 1937, Paul Green’s The Lost Colony premiered at 8:15pm in the Waterside Theatre in the Cittie of Ralegh State Park on Roanoke Island. It was scheduled to run on Sundays, Mondays and Tuesdays from 4 July through Labor Day on 6 September and for other days as scheduled on the 350th Anniversary of the Birth of Virginia Dare Gala Celebration—for a total run of 37 performances. There was one rain-out, but there was also one additional back-to-back performance on the 18th of August—the night President Franklin Roosevelt attended the show. All tickets were General Admission; Adults $1.00; children under 12 at 25 cents each. Seating capacity was 3,200. The show earned enough money to pay all bills and had enough left over to underwrite the 1938 season. Bradford Fearing and his many supporters had succeeded.

On opening night, the audience witnessed what Paul Green described as:

THE LOST COLONY

“An Outdoor Play in Two Acts”

(WITH MUSIC, PANTOMIME AND DANCE)

The 1937 production of The Lost Colony reflected the era in which it premiered. While the depression in the country was lessening in some areas, it was still harsh. The threat of war in Europe continued to escalate, and while Americans remained divided about the possibility of United States involvement, they were uneasy. For many, if not most, their religious faith helped them cope. Paul Green wrote his play for that audience. The music and the characters not only fit the Elizabethan Period of the play, they fitted the 1937 audience as well.

***

Opening Night, 4 July 1937—An Audience-Eye View

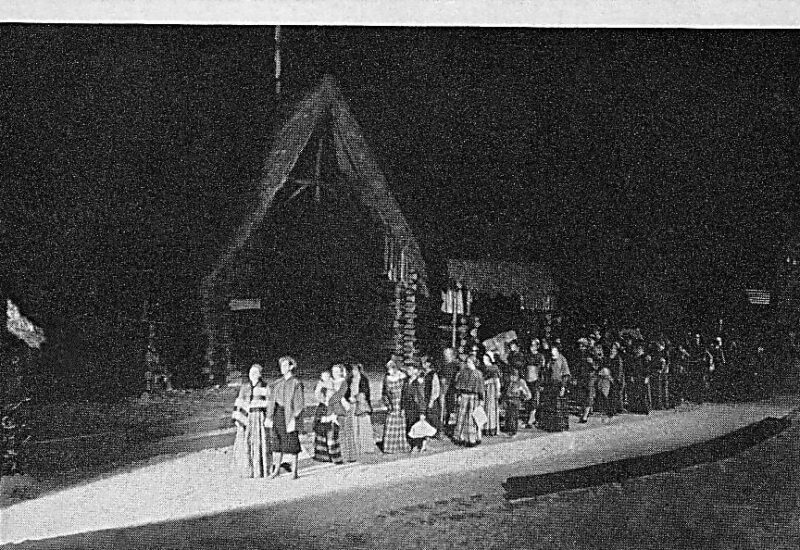

To get to the theatre in 1937, audiences drove or took a shuttle to the north end of Roanoke Island; parked in one of several parking lots, entered through the Cittie of Ralegh State Park, and strolled through the grounds to the palisaded theatre. The pleasant and inviting smell of juniper and pine created a sense of time-travel as visitors strolled through the park.

***

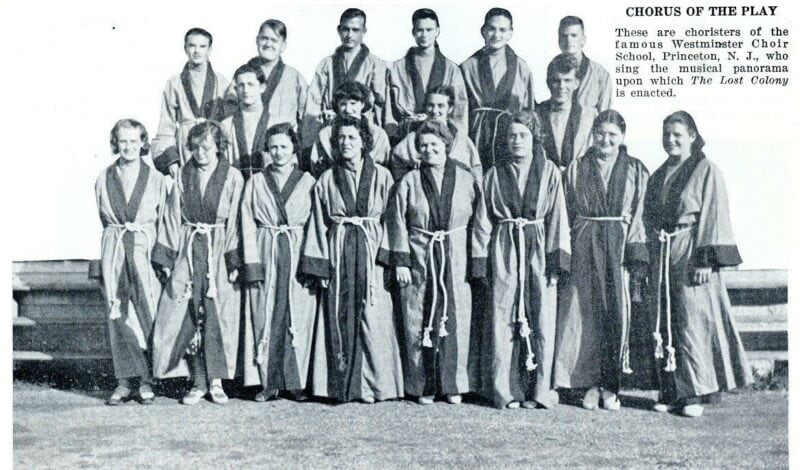

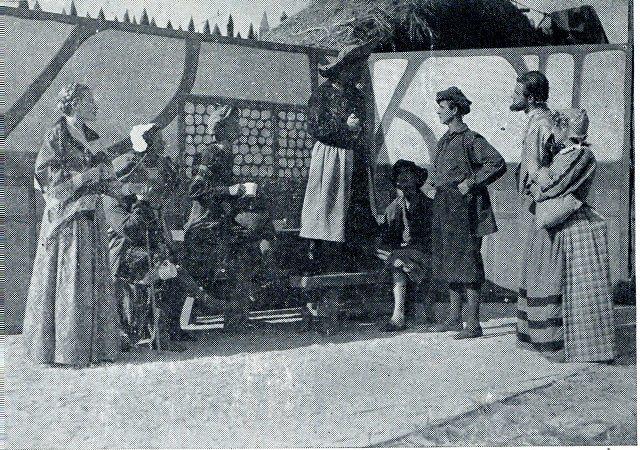

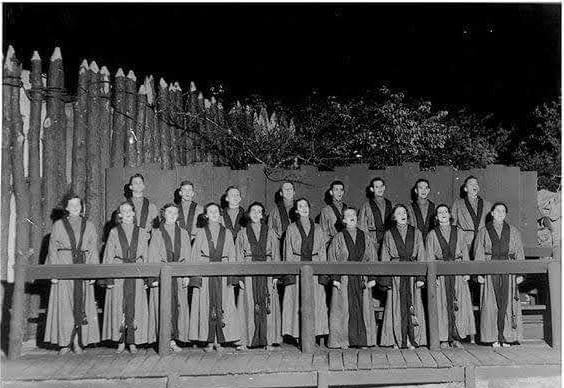

Paul Green’s The Lost Colony, 1937, Westminster Choir Singers. Paul Green constructed The Lost Colony against a musical background of 16th century hymns, ballads, carols, and original music by Lamar Stringfield which contribute mood, tempo and color of the production. The production was scored. The Chorus sang from a choir section on House right and in some scenes did not appear on stage or in the lights. The organ was located beside the chorus but could not be seen by the audience.

THE ORGAN MUSIC: At 8:15pm the view across the Roanoke Sound was almost total darkness. The Wright Memorial light could be seen, and the stars twinkled enhancing the feeling of loneliness in the space beyond.

THE ORGAN MUSIC: At 8:15pm the view across the Roanoke Sound was almost total darkness. The Wright Memorial light could be seen, and the stars twinkled enhancing the feeling of loneliness in the space beyond.

The organ music was scored throughout the play as needed, underscoring the pantomimes; establishing and enhancing ethereal, spiritual, frightening and happy moods; absorbing space with volume, and with less volume and slower tempos amplifying the sense of a loss that became a victory. Welcome to the outdoor Cathedral.

***

8:14 pm, The house lights fade out as the play begins.

The Lost Colony: The Prologue—An unseen chorus, an organ, a Minister, Speaker and the Historian. As the house lights dim out, the chorus fills the darkness singing O God That Madeth Earth and Sky followed by the appearance of a Minister under a spot light, who prays in memory of the lost colonists and their search for freedom & democracy; followed by the unseen chorus, singing, This Was The Vision; followed by the Minister, presenting Paul Green’s now famous, The Dream Still Lives poem; followed by the chorus chanting, Domini Est Terra, [The Earth is the Lords], followed by the Speaker who addresses the audience, reminds the people that Roanoke Island is the site of America’s Spiritual birthplace and encourages the audience to renew their faith in the dream of freedom—as the lights crossfade coming up on the Historian.

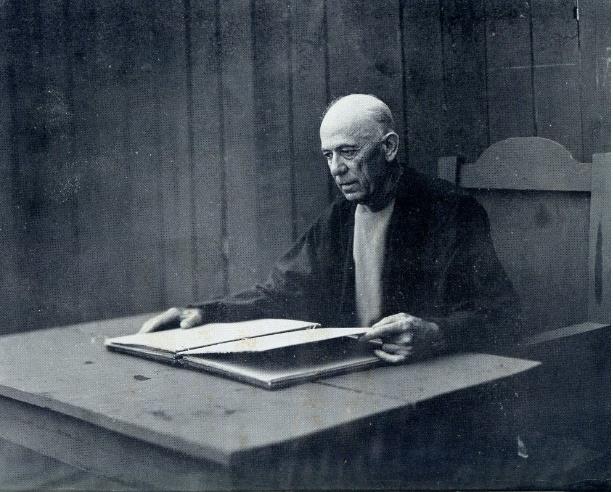

HISTORIAN: [Jack Lee, professional actor from the New York Federal Theater Group]. Seated at the Historian’s desk, located house left between the side Stage and main stage, the Historian tells the story of the play, one scene at a time, mostly before each scene. The use of a storyteller is a characteristic of the pageant form and is also very Brechtian. Following the Prologue, he introduces the first scene— “The Arrival on Roanoke Island of Sir Walter Ralegh’s reconnaissance voyage led by Amadas & Barlowe, and their meeting with the Indigenous People.” It is a pantomime, underscored by original music written for the play for the organ and drums, and explained by the Historian.

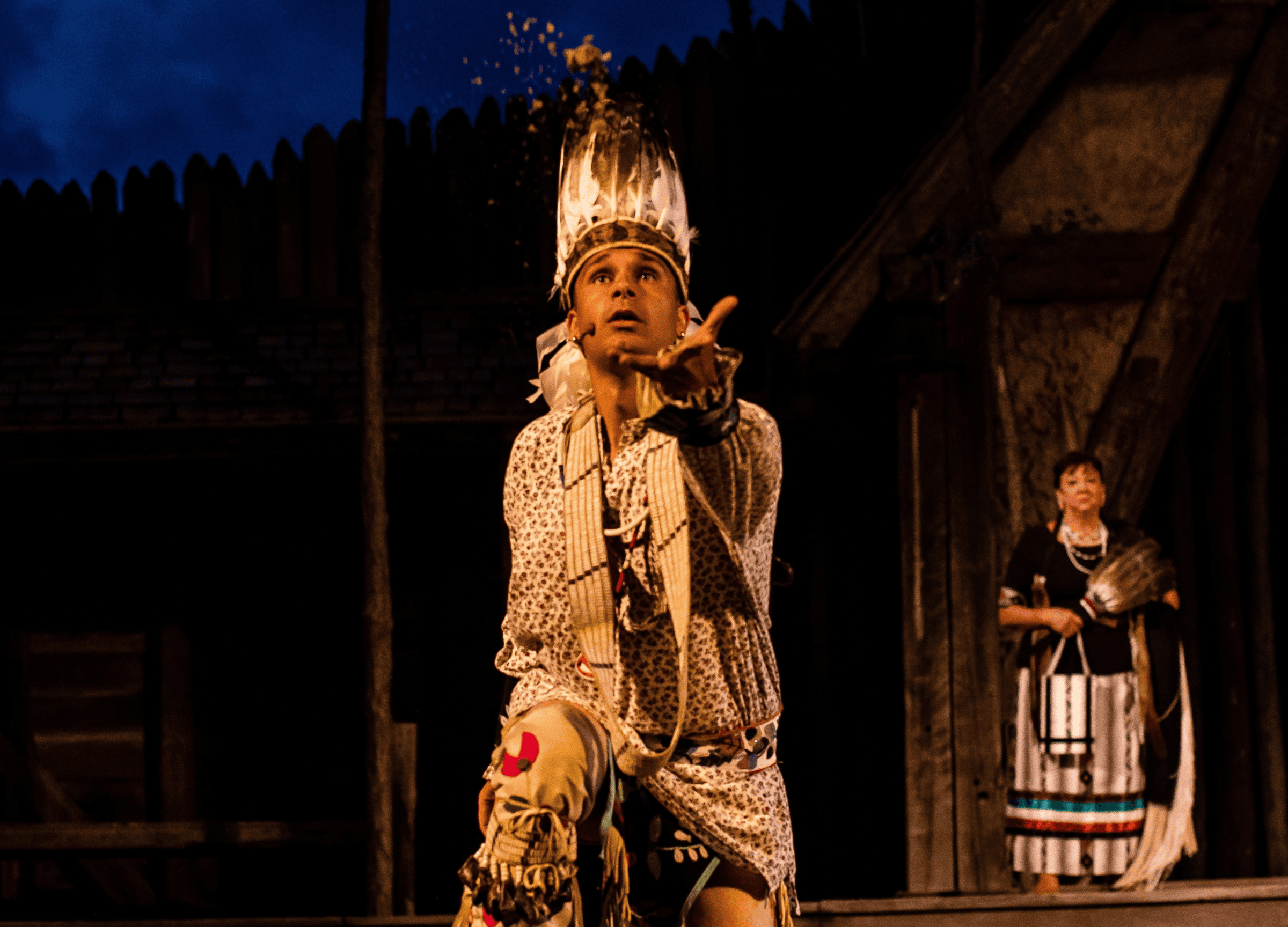

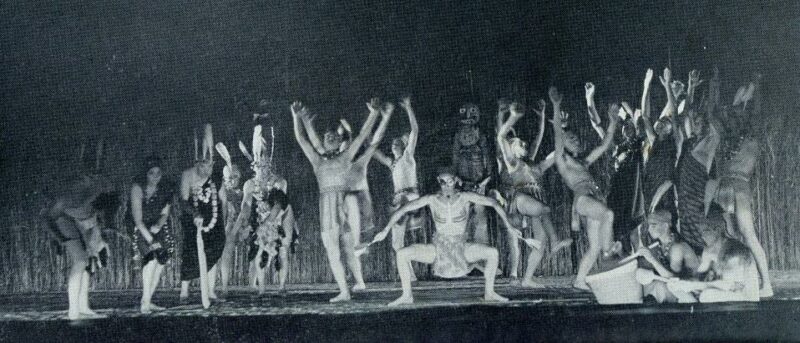

The Corn Harvest Celebration pantomime—The Medicine Man [Fred Howard, UNC-Chapel Hill choreographer, dancer] leads the young men and women in a wild and frenzied Celebratory Dance, he having the solo spot; Organ accompaniment and Native Drums start slowly and build steadily to a wild frenzy, and loud volume, suddenly interrupted by the sounds of horns and gunshots as prelude to the Arrival of Amadas [Robert Atkinson, local] and Barlowe [Gilbert Mister, local].

HISTORIAN: [speaking over the pantomime and the organ music, explaining action as it happens on the main stage— the Indigenous People were afraid of Amadas & Barlowe, and ran away; but the English finally persuade them to return by giving gifts to Granganimeo [Orlando Scharff, local] who accepts the presents and in return gives the English fish, corn and melons to take back to their ships. Amadas officially takes possession of the land. (HISTORIAN READS IT ALOUD) The pantomime continues with the Historian overlaying explanations as lots are drawn to determine who will return to England with the English— Manteo [Charles Overman, local] & Wanchese [Charles Dumont] are selected. Amadas & Barlowe exit, followed by most of the Natives, but leave the Cross they planted. Manteo’s wife and child go to the Cross, as the scene ends.

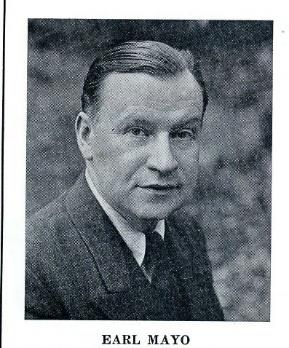

HISTORIAN: Takes the play back to England after Londoners have learned about Amadas & Barlowe’s discovery and have seen Manteo & Wanchese. This transition scene introduces Old Tom [Earl Mayo, professional actor from New York, WPA Federal Theatre] who is both drunk and in trouble with the Royal Guards. Old Tom’s soliloquy is a self-introduction that highlights Ralegh’s success on Roanoke, Manteo & Wanchese in London, and pipe smoking. He sings, Hast Thou Heard What Wise Men Say; is interrupted by Royal Guards, and talks himself out of being arrested. He sings A Man is Down, But Never Out. Old Tom is a well-educated man, down on his luck, but is also a source of comic relief in the play.

HISTORIAN: Takes the play back to England after Londoners have learned about Amadas & Barlowe’s discovery and have seen Manteo & Wanchese. This transition scene introduces Old Tom [Earl Mayo, professional actor from New York, WPA Federal Theatre] who is both drunk and in trouble with the Royal Guards. Old Tom’s soliloquy is a self-introduction that highlights Ralegh’s success on Roanoke, Manteo & Wanchese in London, and pipe smoking. He sings, Hast Thou Heard What Wise Men Say; is interrupted by Royal Guards, and talks himself out of being arrested. He sings A Man is Down, But Never Out. Old Tom is a well-educated man, down on his luck, but is also a source of comic relief in the play.

The scene segues into the Queen’s Garden scene.

Queens’ Garden Scene—Commoners enter while the chorus sings, We Come From Field And Town—with organ accompaniment.

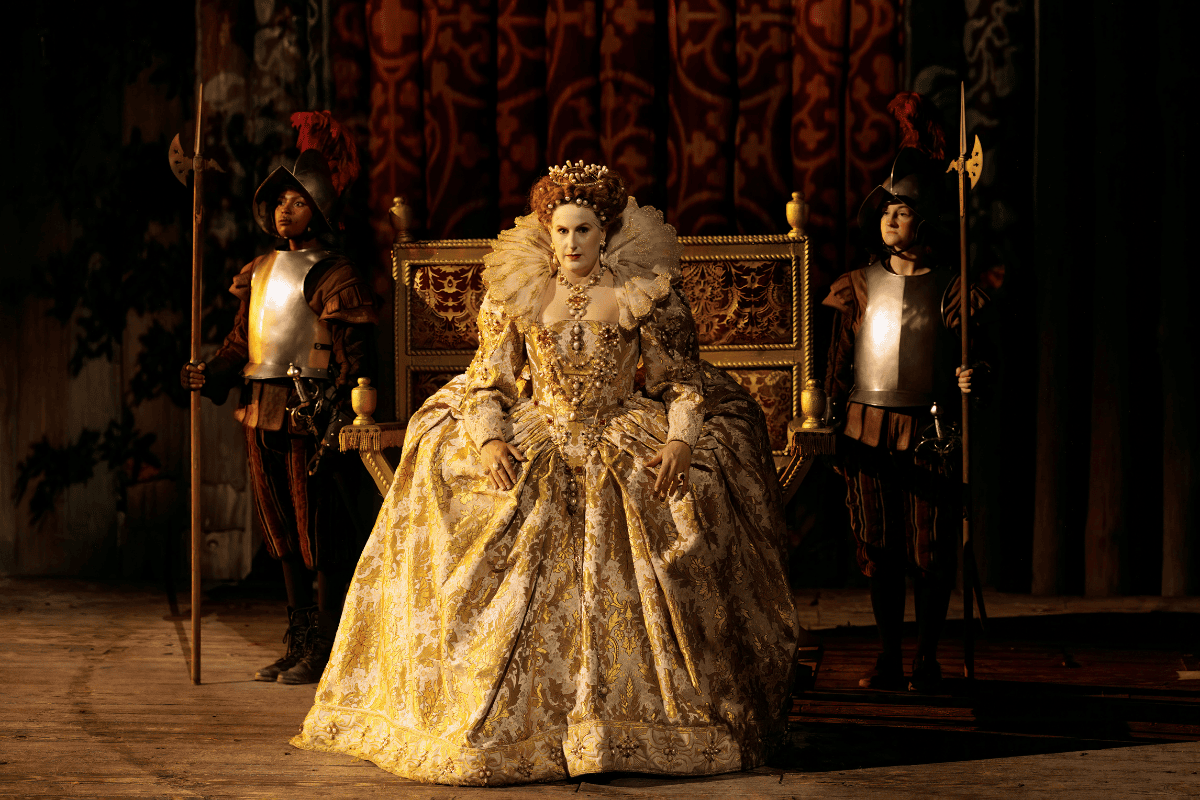

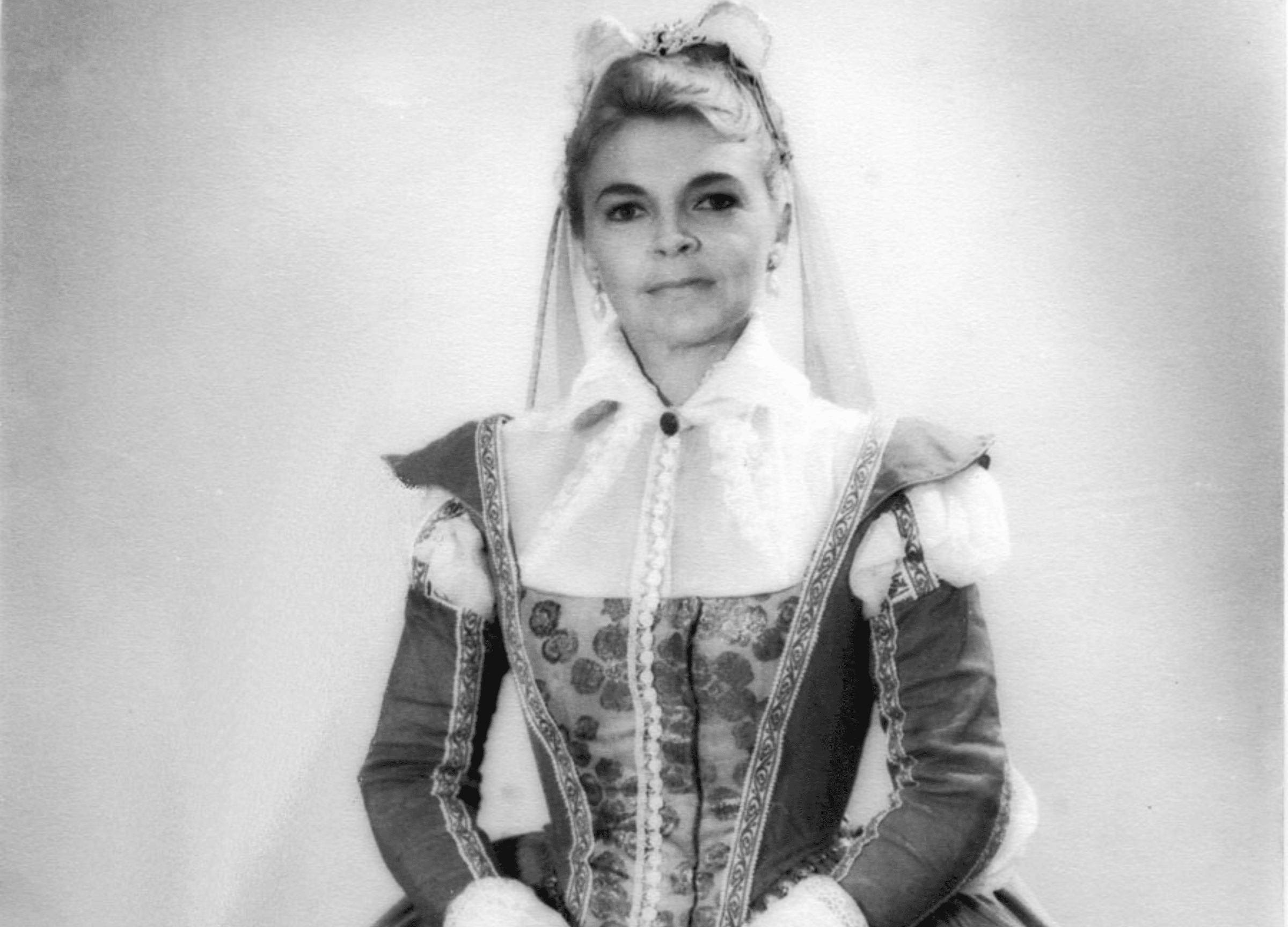

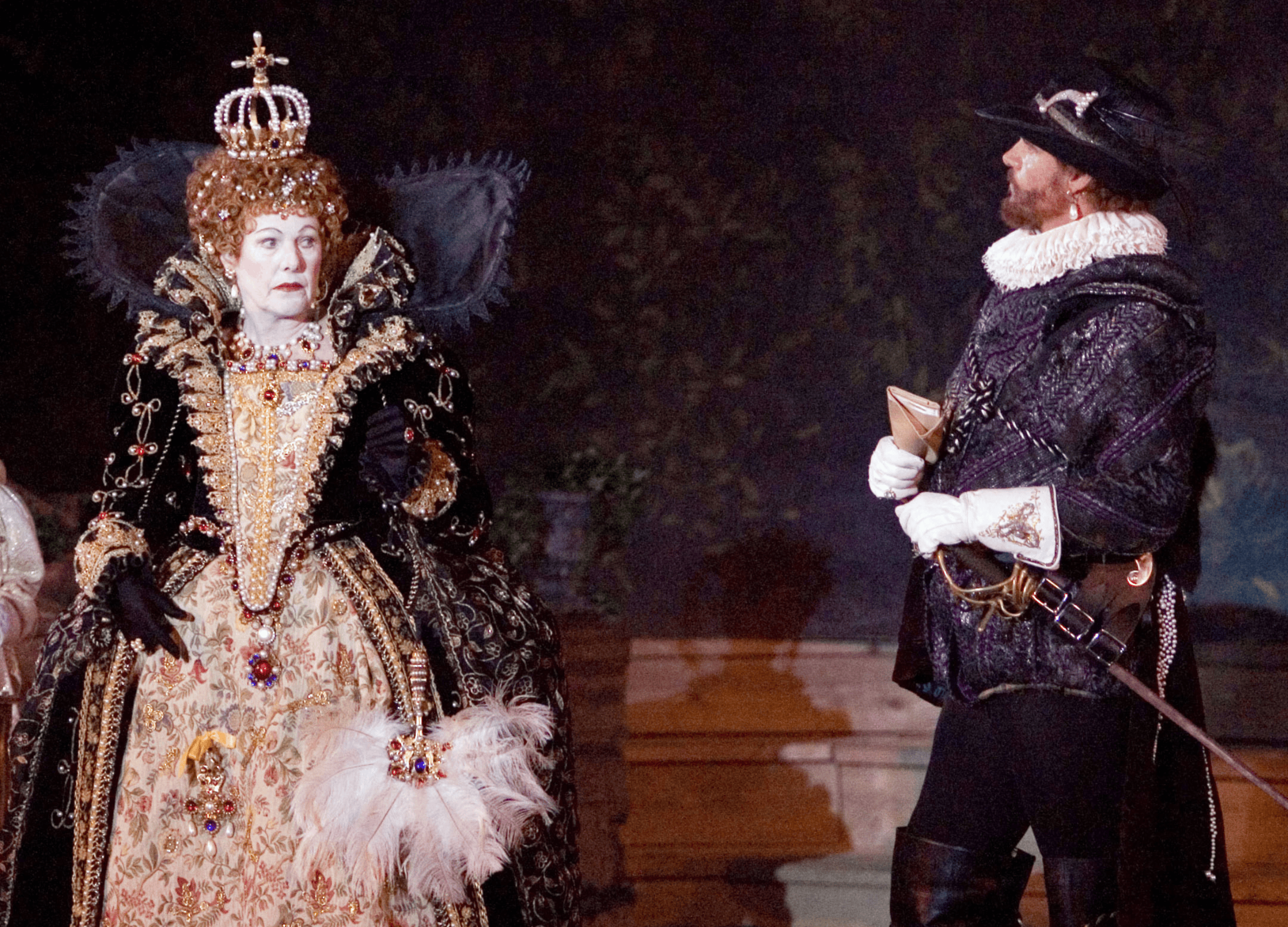

Garden Scene—The Master of the Queen’s Ceremonies [Sam Hirsch] enters and welcomes the people to the Garden Party; announces the entrance of the Queen [Lillian Ashton, English actor with NY Federal Theatre]; Organ fanfare. Presents Amadas & Barlowe who in turn present the turf from Roanoke Island to the Queen;

Presents John White [Judson Langill] who gives the Queen his New World Drawings and presents his daughter Eleanor [Katherine Calé, English actor with the NY Federal Theatre] to the Queen;

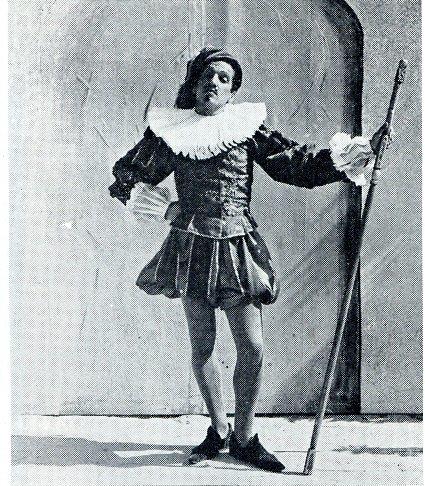

The Master of Ceremonies presents Sir Walter Ralegh (Anthony Roberts, UNC-Chapel Hill)

Ralegh presents Manteo & Wanchese to the Queen who attempts to smoke Manteo’s pipe, but chokes; recovering, she names the new land Virginia and exits.

The Master of Ceremonies lures the crowd to the off-stage repast, leaving only Ralegh on stage alone to participate in a series of skillfully layered, plot-&-character-driven mis-en-scenes:

A dream ballet with organ accompaniment— Milkmaids and Sir Walter Ralegh;

Followed by a short scene with William Shakespeare [Eugene Langston] who asks Ralegh to include him on the next voyage; but Ralegh convinces Shakespeare to remain in England and continue his writing instead, further promising to put the young writer in touch with Sir Philip Sidney.

Ralegh remains on stage as the Historian brings the focus back to colonization for another short scene:

HISTORIAN: Comments on Shakespeare’s remaining in England, and on John Borden [Raoul Henry, NY Federal theatre actor] who is in love with a lady above his station and wants to go to Roanoke on the second voyage.

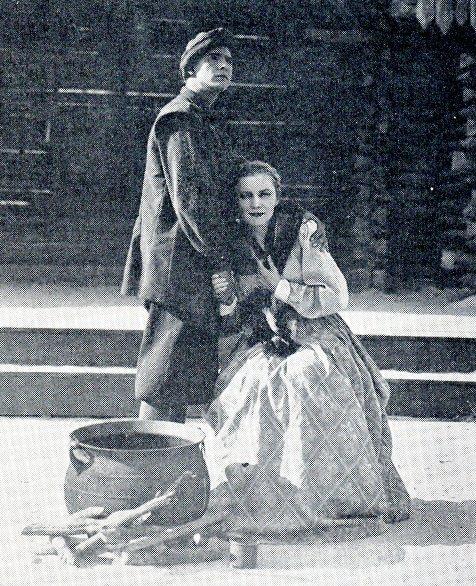

Borden enters to find Ralegh on stage alone. Soon Eleanor [English Actor in New York, Katherine Calé] enters to speak with Ralegh—she wants to go to Roanoke as well and is surprised to find Borden with Ralegh.

The script continues to bring the principals together to advance the plot; the Queen [Lillian Ashton, English Actor in New York] re-enters and informs Ralegh she will send Ralph Lane [Tom Fearing, local] to govern a colony of explorers on Roanoke Island.

The Queen exits and Ralegh starts to, but Old Tom wakes up and the two of them have a discussion—Ralegh gives Old Tom money and says he might need him for Roanoke; Ralegh exits off-stage & Tom exits to the pub.

HISTORIAN: Following through with the colonization of Roanoke established in the Queen’s Garden scene and the mis-en-scenes, the Historian gives a summary of Governor Ralph Lane’s eleven months in the New World, focusing on the growing hostility between Lane and Wingina, and resulting in Lane’s attack on the village and the murder of Wingina. [This narration of historical information is littered with inaccuracies, most of which have been corrected in the modern version of the play.]

The Indian Medicine Man [Fred Howard, UNC-Chapel Hill] calms the fears of King Wingina [Orlando Scharff, local]. In the pantomime, Lane & his men attack the Indigenous People and Lane [Tom Fearing, local islander] personally kills Wingina; the natives scatter; Lane and his men move to the mainstage and mount the guard, concurrently with the Medicine Man and the survivors of the attack arming themselves and counterattacking the fort on the main stage—only to retreat again—as the organ stops and the light comes up on the Historian again.

HISTORIAN: Though repelled, the Roanokes attacked the fort again; poisoned wells, spoiled cornfields and drove the game away. When Sir Francis Drake arrived, Lane and his men abandoned the fort and returned to England. A few days later, Sir Richard Grenville arrived with supplies, but finding the fort deserted, he left 15 men to hold it and returned to England.

Despite this failure, Ralegh persisted in his dream—as did Eleanor Dare, John Borden and even Old Tom. Ralegh outfitted three small ships and on 8 May 1587, the expedition assembled at Plymouth for the voyage to the New World.

The scene is played on the mainstage corner at house right—the outside of a tavern at the Plymouth docks. The colonists meet at Plymouth to depart for the New World. Pilot Simon Fernando [Sam Hirsch] tries to dissuade them; John Borden [Raoul Henry] encourages and inspires 120 of the colonists— including Old Tom— to go with him to the New World. Ralegh arrives with John White, his daughter Eleanor, and her husband Ananias Dare [Martin Kellogg, local]. Ralegh speaks to the assembly and enthusiastically supports their role in the foundation of English America. He assures them of his faith in their pilot Simon Fernando, after which all the settlers exit to the ships, singing O Farewell England. Ralegh remains on stage, his face lifted in prayer as the unseen chorus hums softly at first, gradually louder until the words can be understood— We Commend To Thy Almighty Protection A black out concludes Act I.

A 15 MINUTE INTERMISSION—Drinks & packaged snacks were brought into the house for sale—like at a baseball game.

Act 2

The audience is summoned to their seats by the sound of the organ as the lights come up on the chorus, singing God Is Our Hope And Strength.

HISTORIAN: After a long & stormy voyage, the colony arrives on Roanoke Island and begins a search for the holding party left by Sir Richard Grenville the year before.

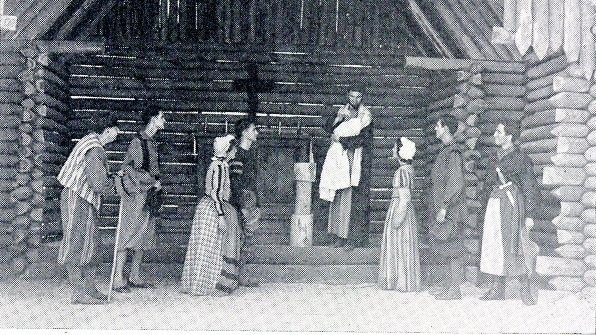

ARRIVAL SCENE: The small landing parties which include John Borden and Ananias Dare meet on the mainstage, which was Ralph Lane’s Fort and, with a little cleanup, will still be habitable. Manteo & Wanchese are with the landing parties. A member of Wingina’s Tribe enters from the forest and reports that Lane’s soldiers killed Wingina & that Wanchese is now the new King. Wanchese leaves with his people, but Manteo remains with the English who debate whether they should remain on Roanoke or remove to another site. Because of Manteo’s advice and support, they decide to remain on the island.

The Search Parties exit to activate the unloading of the ships, as Old Tom enters for a soft-comedic solo act during which he tells of some of the discomforts during the eight-week voyage from England. Looking around the cabins, Old Tom discovers the corpse of one of the men from the earlier expedition—and is frightened. His screaming attracts Governor White and a group of colonists. The settlers cleanup the fort, and give thanks to God for their safe arrival. Wanchese returns and orders them to leave the island. They ignore his threat and remain determined to follow Sir Walter Ralegh’s directive to live side-by-side with the Indigenous People and remain non-invasive.

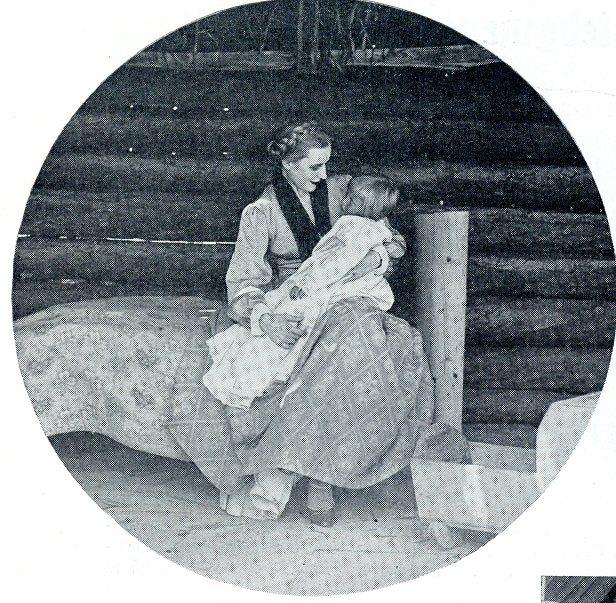

FISHNET SCENE: Opens with a group of colonist women mending fishnets and grinding meal. They sing as they work— Adam Lay Y-bounden; Eleanor Dare is about to give birth. The ladies create a picture of life at the settlement, for which author Green creates another set of mis-en-scenes. Taking a short rest from his job of carrying water to the fields, Old Tom drops in with his new ladylove Agona who is a member of the local tribe. The Fishnet ladies enjoy teasing Tom, who quickly returns to work when he hears John Borden’s voice calling for him. A second mis-en-scene follows. This time with Manteo, his son Wano, and the young English boys he has been teaching to fish. In yet another short scene, John Borden and Manteo discuss Wanchese’s attacks on the settlement, and suddenly, Old Tom returns, rushing to the Chapel, shouting “Hear Ye”, rings the bell and announces that Eleanor Dare has given birth to a baby daughter.

Colonist women mend fishnets in front of the fort’s chapel.

Colonist women mend fishnets in front of the fort’s chapel.

Old Tom and his ladylove, Agona, stopover to greet the ladies mending the nets.

HISTORIAN: Manteo was baptized on 13 August; Virginia Dare on the 20th.

CHRISTENING SCENE & GOVERNOR’S FAREWELL: Church Service for Virginia’s Christening; singing of Let Little Children Come To Me; By Water & the Spirit sung by cast members on stage plus the chorus; after which the colonists drink to the child and dance; Governor White, who is returning to England for supplies, announces that he is leaving Ananias and Eleanor Dare and John Borden in charge. Old Tom sings, O Once I Was Courted to Agona as the scene ends.

HISTORIAN: John White’s voyage back to England was difficult. He did not arrive until 8 November 1587, and by then, Spain was preparing to attack England with a great Armada—and the Queen needed all English ships for her defense.

Queen’s Chamber Scene: Governor White and Ralegh are meeting with the Queen & Lord Essex, begging permission to send two of Ralegh’s small ships to relieve the colony on Roanoke. She finally agrees, but seconds later a royal messenger arrives with the news that Spain’s Armada is in the channel—and no ship can sail until the Armada is defeated.

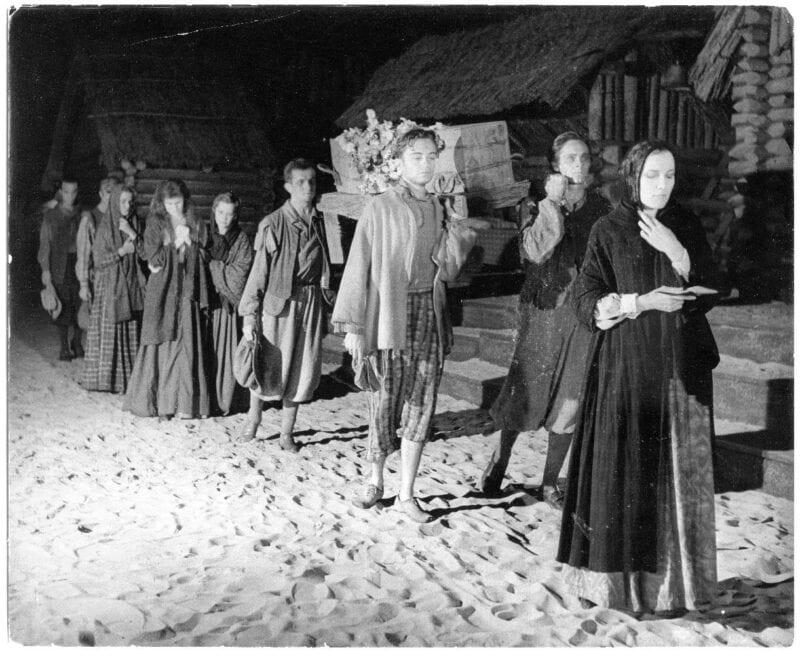

HISTORIAN: Back on Roanoke, a funeral is being held for Margery Harvey’s child. The organ plays, Dead March.

HISTORIAN: The colony has suffered, many have died, including Ananias Dare. The specter of starvation faces them on their second Christmas. Eleanor sings a lullaby to the baby Virginia—Jesus, From Thy Throne on high, with organ & choral accompaniment.

Father Martin is desperately ill. Old Tom & Agona arrive with berry candles—they plan to marry as soon as Father Martin is well enough. The Yule Log arrives, and the colonists sing The Holly & The Ivy and try to be optimistic—but it does not work. The Chorus sings All Under The Leaves Of Life, with organ accompaniment. The colonists pray to God—but everyone is hungry; most are sick; the sentinel guarding the fort quits; a riot is about to break out. Father Martin tries to calm the settlers.

But when John Borden returns, he settles the group of starving colonists; convinces them that tomorrow is a better time to discuss the situation. They return to their cabins to rest. Mad Marjory sings Sir Walter Ralegh’s Ship and is taken back to her cabin. Borden holds back on the news that Manteo is dead.

The Pot Scene: Borden and Elinor discuss their love for each other, their commitment to Sir Walter Ralegh, and the dire situation of the near-starving colony. They decide they will never permanently desert the Roanoke settlement and the dream of democracy; but to survive the winter, they must leave it temporarily and accept the offered hospitality of Manteo’s Tribe, the Croatoans. Manteo is dead, but his tribe has asked John Borden to be their leader. They plan to discuss their idea with the colonists tomorrow. Eleanor goes to bed; Borden sleeps on the ground by the pot; and Old Tom is on guard duty on the parapet. Old Tom’s soliloquy—Roanoke Thou has made a ‘man’ of me, is softly underscored with peaceful music, giving hope, Sleep, Sleep, O Pioneers, with organ accompaniment. But it is rudely interrupted by an impassioned Runner who arrives with vital news: a Spanish ship has anchored in the inlet. The bell is rung; the settlers reappear; the Runner reports the news; the settlers decide to leave the fort and go to Croatoan—but the are firm in their commitment to return in the spring. They hastily collect their bare necessities and form a line behind John Borden and Eleanor Dare on the mainstage in readiness of their departure.

HISTORIAN: [narrating] In the cold hours before dawn, the colonists begin their march into the unknown wilderness. The scene is a pantomime with organ & drum accompaniment—The March Into The Wilderness—as the performers and chorus sing slowly at first, then the tempo and volume increase as the settlers gain strength and renew their commitment to their dream of democracy. The group walks across the main stage and up the ramp at House-left, singing as they go—elevated with a new strength of commitment by the time they reach the ramp, and exit singing into the forest.

HISTORIAN: [when all the colonists have exited, but their shadows can still be seen outside the theatre in the dimly lit trees] Delivers Paul Green’s now famous The Dream Still Lives! Poem:

“Now down the trackless hollow years

That swallowed them but not their song

We send response—

“O lusty singer, dreamer, pioneer,

Lord of the wilderness, the unafraid,

Tamer of darkness, fire and flood,

Of the soaring spirit winged aloft

On the plumes of agony & Death—

Hear us, O hear!

The dream still lives!

It lives, it lives,

And shall not die!”

At the end of the poem, the organ strikes in a bold announcement.

The light dies from the Historian,

and gradually comes up on the chorus singing, O God That Madeth Earth and Sky—

At the end of the number, the last Amen—the lights come on in the Amphitheatre.

The audience leaves the theatre, walking, almost in a column like the colonists on stage, along the loop road through the Cittie of Ralegh ‘s treed village; walking to their cars and buses to leave the island, still emotionally and intellectually absorbed, suddenly realizing—they have walked in the footsteps of the colonists. Their Dream Still Lives!

Aeolus and Neptune challenge each other

at The Lost Colony’s Waterside Theatre

September 1960

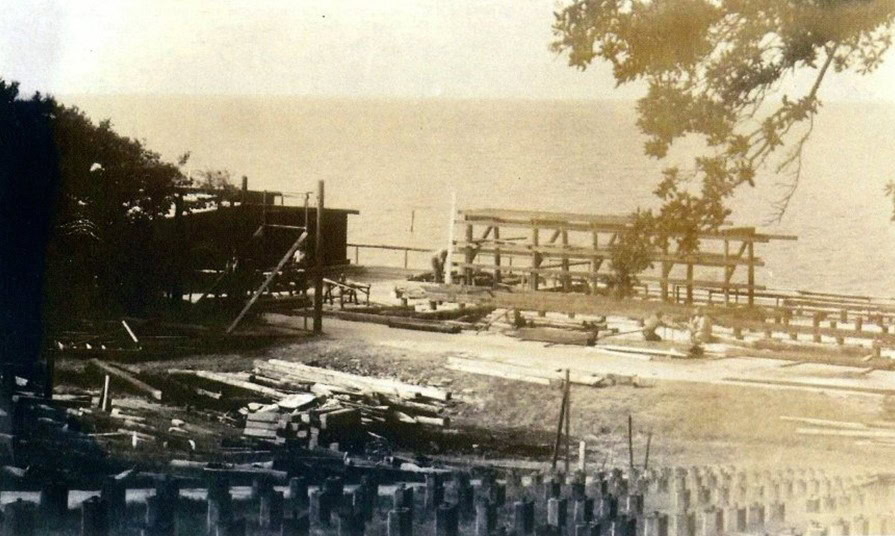

The Waterside Theatre was built in 1937 and used for the performance of The Lost Colony through 1941. Closed during the war years, it was re-furbished in 1946 for a sustained run of Paul Green’s outdoor symphonic drama. During the 1947 season, the theatre was destroyed by fire, but re-built in 6 days and the season continued. Major repairs were effected off-season through the 1950s, and the log structures were replaced with the more historically accurate wattle and daub sidings. But in the late 1950s, Designer-Builder Skipper Bell kept the producers well aware of the fact that a major re-build was needed. Funding, however, would take time.

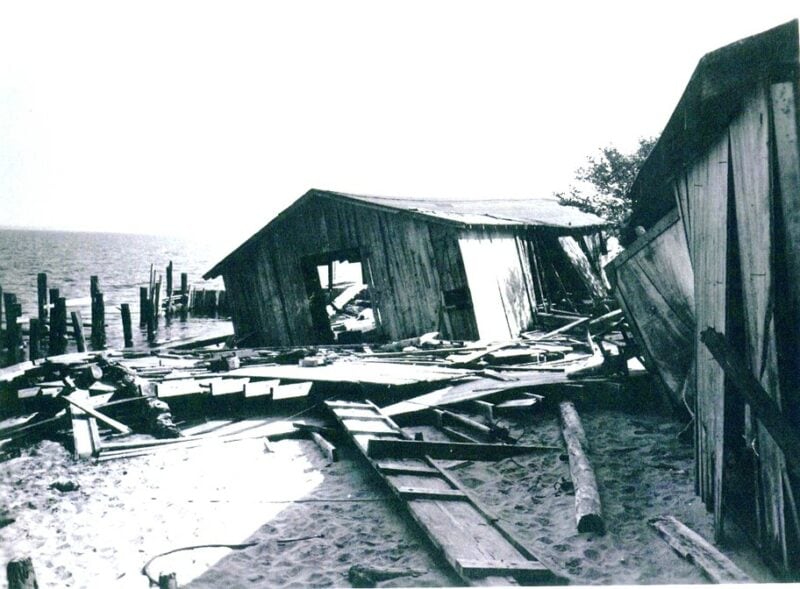

Just after the end of the 1960 season, Hurricane Donna, moving up the coast from Florida where it had wreaked unbelievable havoc, invaded the Outer Banks, and among many other tragedies, destroyed the Waterside Theatre.

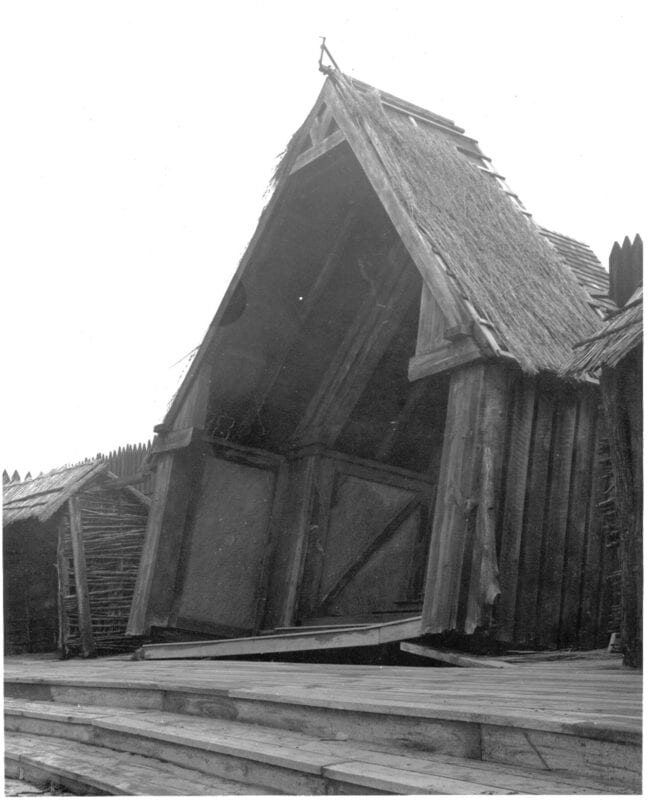

The Permanent Set: First Photos after the storm.

The Chapel has been ripped from the underpinnings; twisted; and lost much of its thatching.

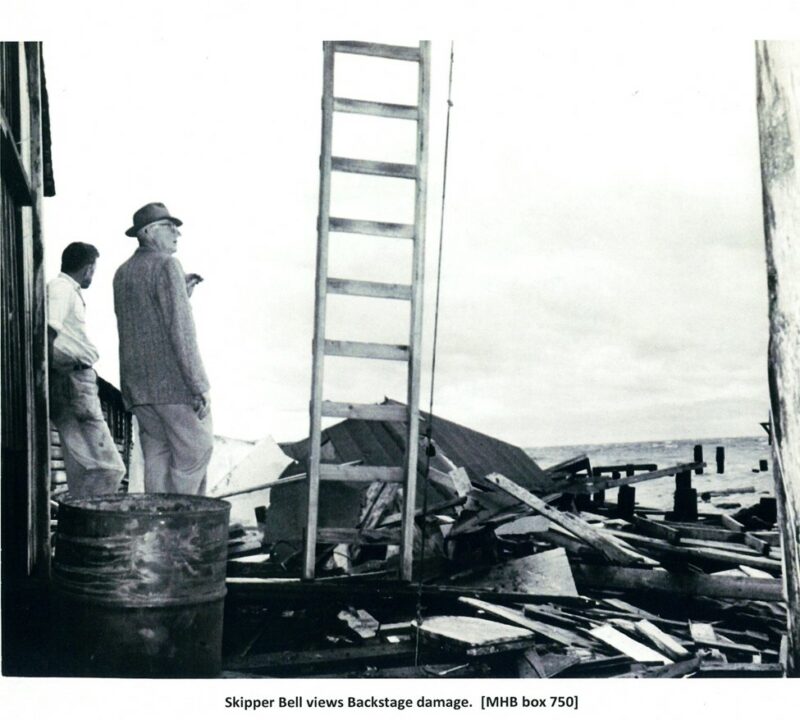

Backstage Left: First Photos after the storm.

The stage Left Prop Cabin centered between a portion of the stage-left side of the permanent on-stage cabin, and on the right side of the parapet. The entire unit is twisted. Behind the structure, the ship-track which parallels the permanent setting is gone, leaving only stub pilings. Similarly, in the water beyond, only stub pilings remain from the deck to Skipper’s Pump House—which has been completely destroyed.

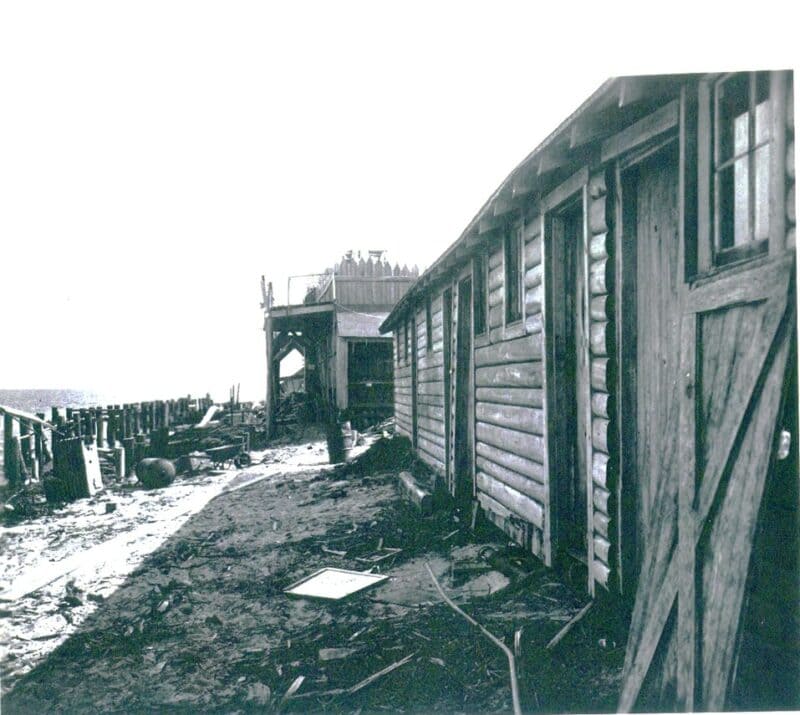

Backstage Right: First photos after the strom.

Skipper Bell [wearing a hat], with one of his helpers, views the storm damage in the area of the Men’s Dressing Room. Some of the decking remains, but the ship track has been demolished. At the top of the photo, the Parapet is leaning and the tallest structure—which is the Chapel—is clearly tilted.

Backstage Right: First photos after the storm.

The photo was shot at the same time as the preceding picture. Skipper Bell [with hat] and his helper backstage-right viewing the damage.

Backstage Right: First photos after the storm.

The structure on the left appears to be one of the Men’s Dressing Rooms. The other roof pieces belong to the other structures built by a similar plan. The possibilities are Skipper’s Workshop, the second Men’s Dressing Room, or even the Costume Shop from Backstage Left.

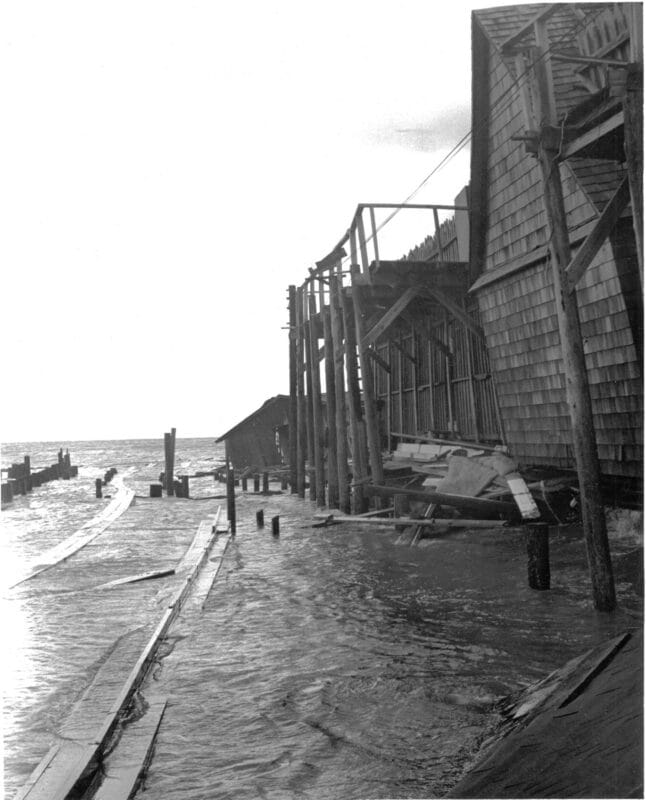

Backside of Center Stage; First photos after the storm.

The tallest structure, the backside of the chapel, is clearly twisted. To the left of the photo, the ship’s track is afloat.

Mid-October 1960 NPS Photos

It is hard to believe, but Skipper Bell and his crew patched, repaired and in a few cases replaced the storm damaged structures and had everything in place for the 1961 season of the production. In the RIHA Archive at the NPS Museum Resource Center, Skipper Bell’s Blueprint he made for the NPS to obtain permission to replace the Dressing Room can be found in the RIHA Collection, Box 233, Catalog # 3430. His drawings for the replacement Dressing Rooms are archived as: MRC-RIHA Box 185; catalog # 3429. Bell and his team repaired and pushed everything else back in place for the 1961 season.

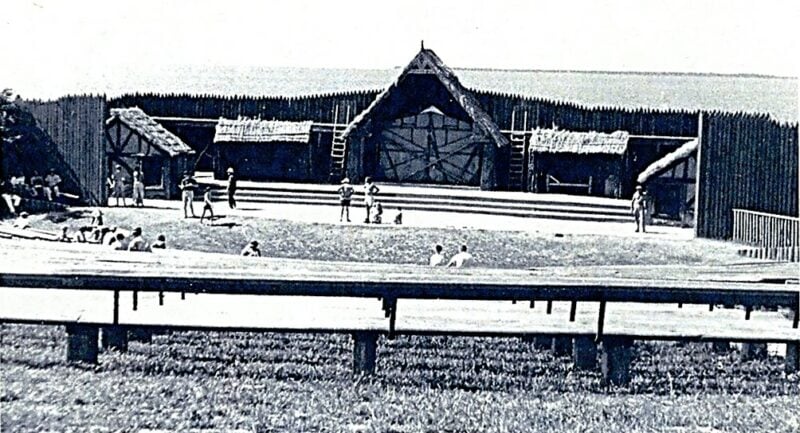

The 1961 Waterside Theatre

\

\

At the close of the 1961 season, Bell began work on the new theatre; stripping everything down, and building a new theatre, stage, backstage and house. He finished everything in time for the 1962 season.

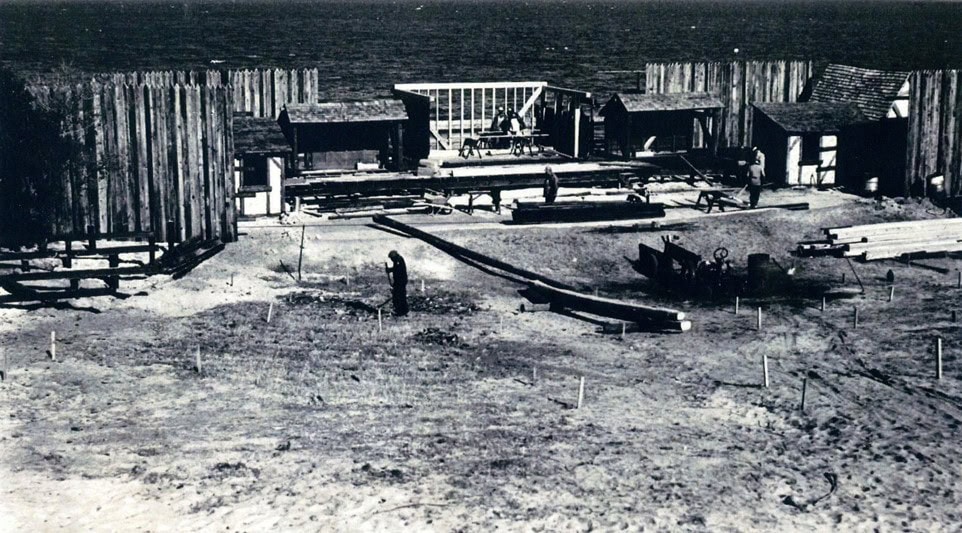

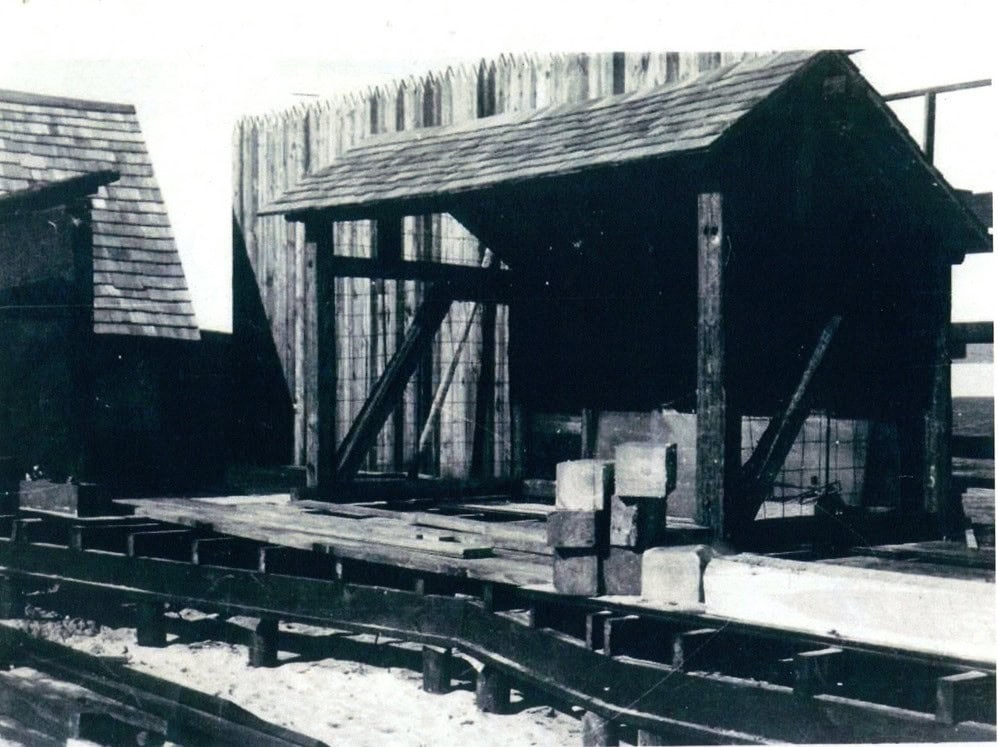

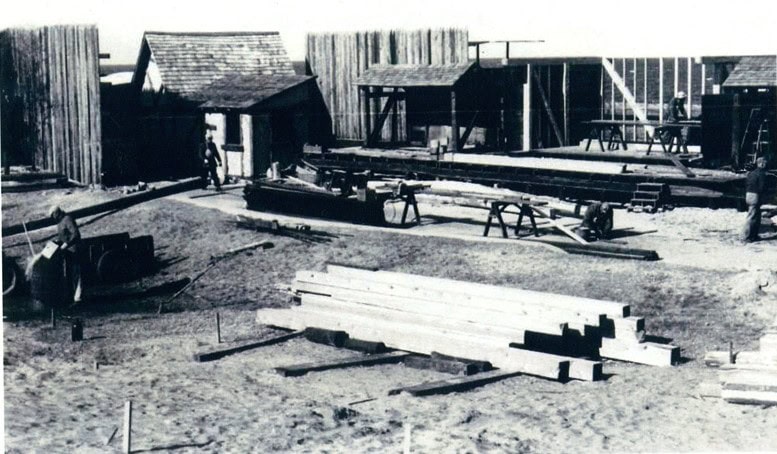

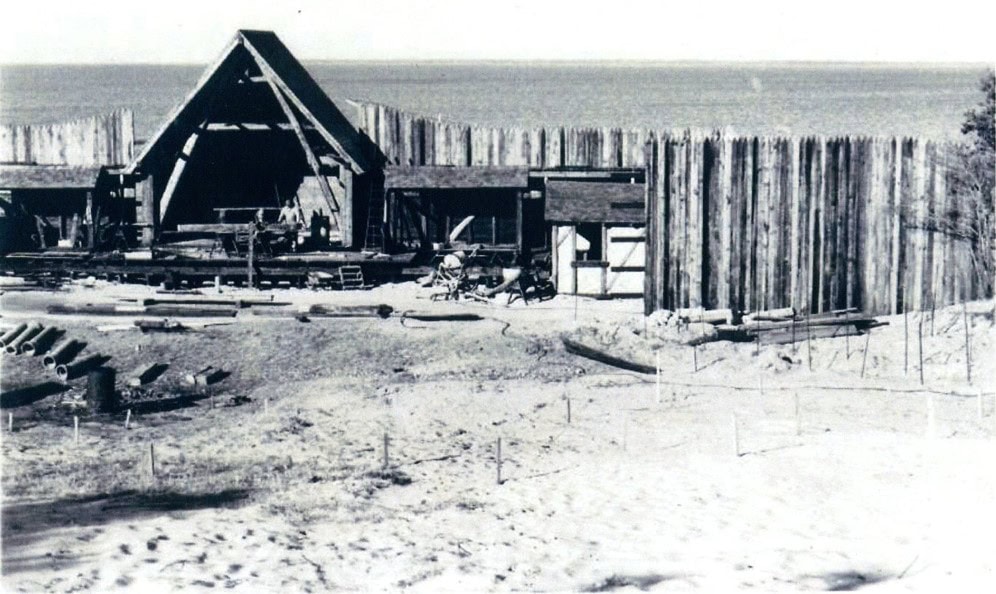

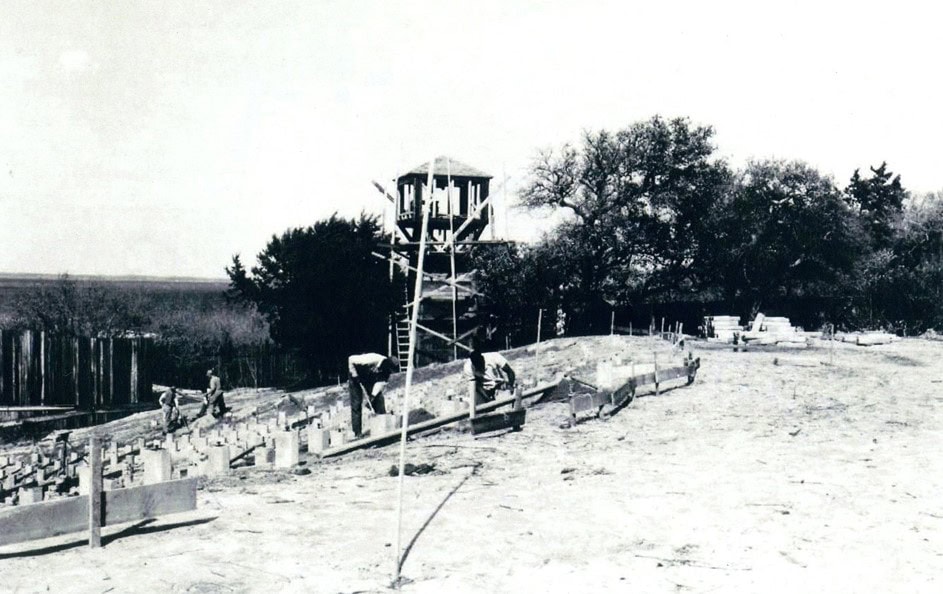

December 1961-1962 Theatre Under Construction: Mainstage

December 1961 House Under Construction

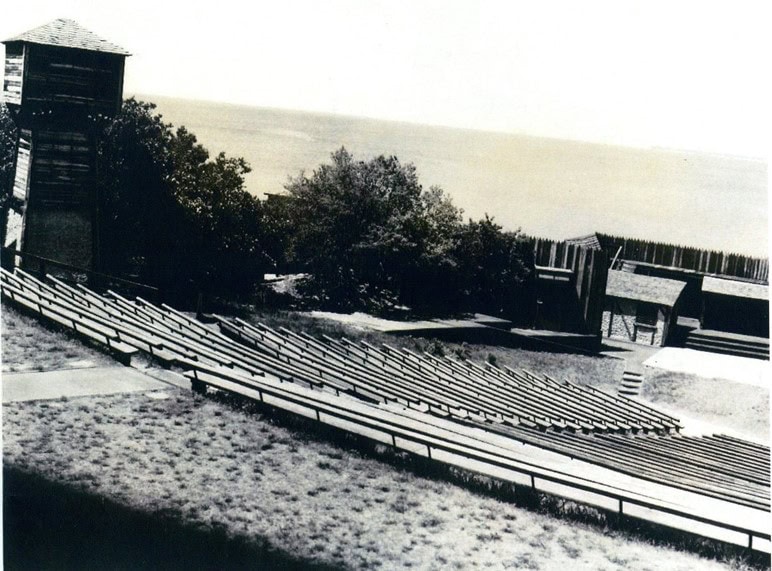

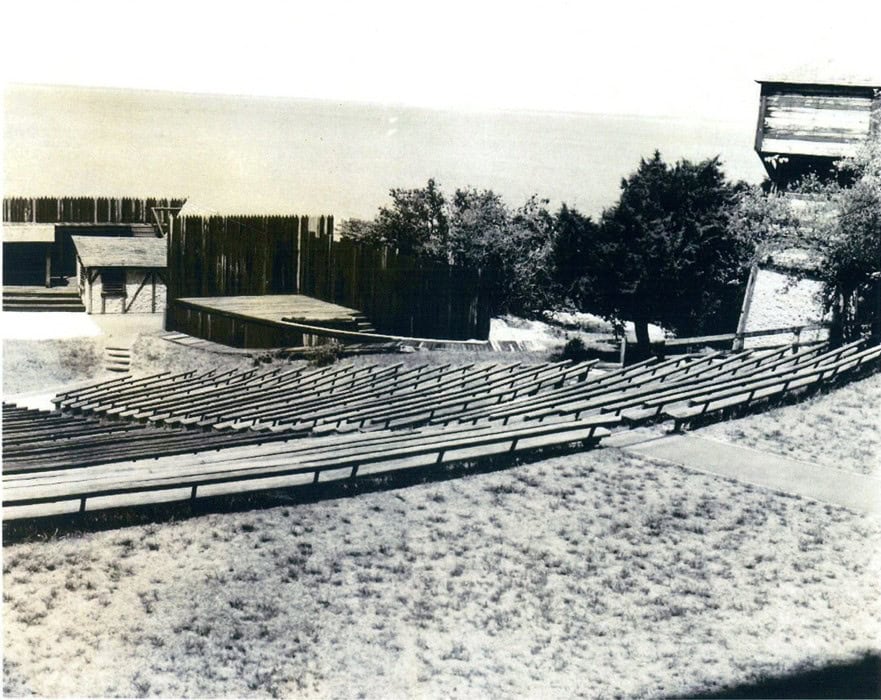

1962 Re-Constructed Theatre- December

The 1962 Re-constructed Waterside Theatre

A few minor changes were made in 1964 at the request of the new director, Joe Layton. A.Q. Skipper Bell died on 11 September 1964. In the 1990s, the theatre was refurbished, following Bell’s designs carefully. The real change was the switch to stadium seating, instead of wooden benches. The 2025 Waterside Theatre remains the House that Skipper Built—Hurricane Donna notwithstanding.

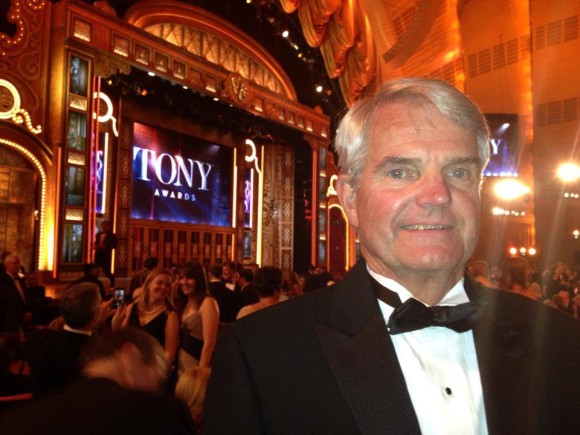

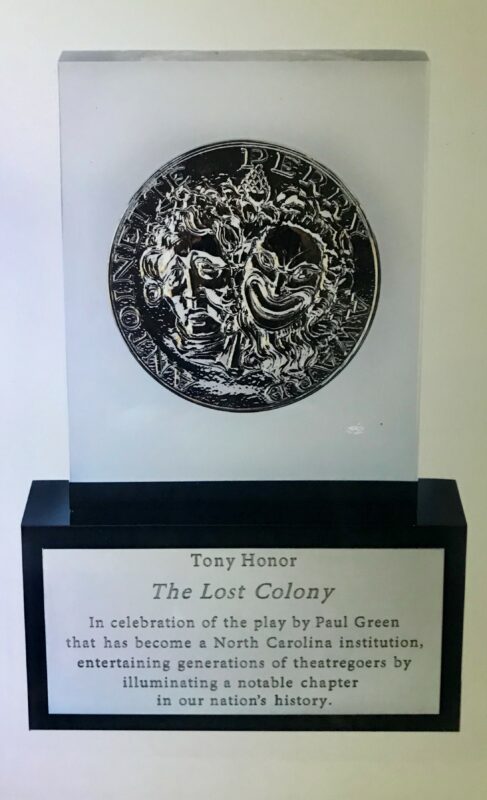

The Lost Colony is the first theatre in North Carolina to be presented a Tony Honor For Excellence In Theatre!

Since 1947, the Tony Award has been the highest award presented for excellence in the American Theatre. On Sunday, June 9, 2013 the American Theatre Wing presented the 2013 Tony Awards at Radio City Music Hall in New York City and The Lost Colony was presented the Tony Honor for Excellence In Theatre. The Tony Honors are presented to individuals and organizations that are not eligible for the annual competitive awards. The Lost Colony has the distinction of being one of the last remaining Federal Theatre Projects and enjoys a rich history which includes many luminaries in the theatre.

After leaving Manhattan, in true theatrical fashion, the Tony arrived at Waterside Theatre on the ship used in the production as the crowd cheered from the theatre seats. Bill Coleman, CEO, and Steve King, Board Chair, proceeded down the ramp and onto the stage proudly holding the prized award, after which it was placed on a pedestal center stage where everyone could admire it. Following a the obligatory speeches, the audience was invited to come on stage and hold the Tony themselves. Pictures were soon posted to locations all over the world. The Lost Colony is the only organization in North Carolina to ever receive such an award and this award belongs to the community of actors, technicians, musicians and dancers who have been a part of the production since 1937, as well as the loyal supporters and sponsors who made it happen. This award belongs to the Dreamers everywhere.

Since 1937, almost 7,100 Keepers of the Dream have helped make The Lost Colony happen each summer. Each of these individuals contributed something in their own way, whether it was on-stage, backstage, in the concession stands, or in the administrative offices. It truly takes a village to produce a show the size of The Lost Colony, and without our alumni the show and institution would just be a distant memory.

The below links contain a list of all Alumni of The Lost Colony. The lists are sorted by last name.

This list is being updated currently to change inaccuracies, grammar, and formatting mistakes. Information for this roster was taken from Souvenir Programs, Stage Manager notes, and additional sources to verify accuracy, but we cannot guarantee that this roster is accurate.

This list was lovingly curated by Lost Colony Alum Mary Salem.

See something on this list that is inaccurate? Let us know below!

Alumni Information

A chance to help us update our Alumni Roster to make it as accurate as possible.

The Vision

“By ‘people’s Theatre’, I mean theatre in which plays are written, acted and produced for and by the people for their enjoyment and enrichment and not for any special monetary profit.”

Pulitzer Prize winner Paul Green wrote those words about The Lost Colony in 1938, a year after its debut. By then, America’s first outdoor symphonic drama was a critical and popular success, proof that “people’s theatre” could work. But this early success was far from guaranteed.

Commissioned by Roanoke Island residents, who had a long tradition of celebrating their place in American history, The Lost Colony was born of a desire to commemorate the 350th Anniversary of the birth of Virginia Dare in 1937.

North Carolina’s Paul Green penned the production, which was a unique combination of drama, song, and dance, while Roanoke Islanders set to work building the magnificent Waterside Theatre on the very spot where the colonists settled. On July 4, 1937, The Lost Colony opened to a packed house, despite the economic hardship of the Great Depression.

The show was intended to run only that one summer. But when Franklin D. Roosevelt attended on August 18, 1937, the nation’s eyes were fixed on the production, assuring that there would be subsequent seasons.

Since then, the production has seen its share of challenges and outright disasters. World War II brought the lights down on the show for four years as German U-boats prowled the sea just off the Outer Banks. In 1947, Waterside Theatre burned to the ground, only to be quickly rebuilt by local residents. And in 1960, Hurricane Donna roared over Roanoke Island, sweeping most of Waterside Theatre into the sound. The Theatre was reconstructed in time for the 1961 season. In 2008, the Costume Shop and most of the costumes burned. In 2020, the pandemic closed the Theatre. Through it all, The Lost Colony persisted and endured.

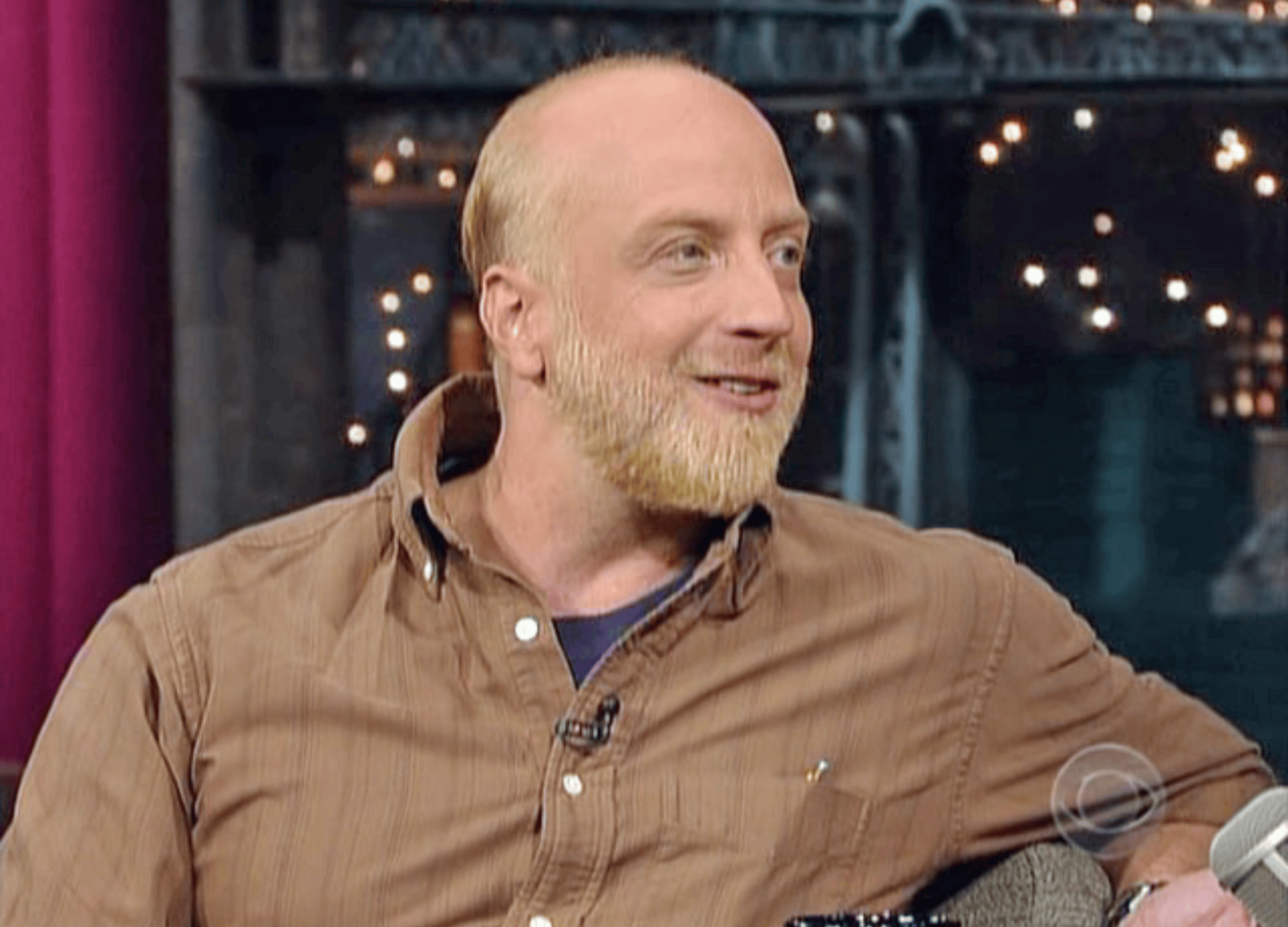

Over 85 years in production, The Lost Colony has long been a state and national treasure. It has served as the training ground for over 5,000 actors and technicians, including such famous personalities as Andy Griffith and Terrence Mann, while entertaining over four million people since its debut in 1937. It has grown far beyond its humble beginnings.

But in the end, The Lost Colony ultimately belongs to the people of Roanoke Island who have cherished and nurtured the drama from its infancy.

Peruse The Lost Colony annual souvenir programs from as far back as 1937. These Souvenir Programs contain a Company list from each year, old production photos, fascinating articles about the Roanoke Colony and the production, some classic Americana ads, and much more.