Roosevelt on Roanoke

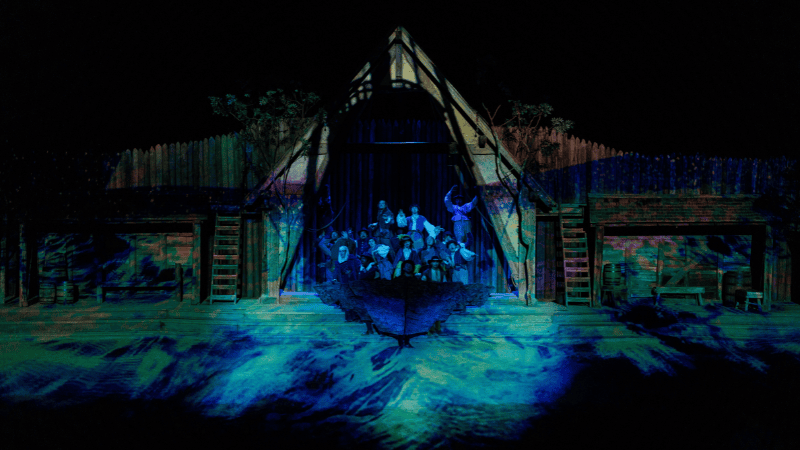

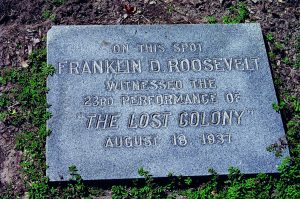

President Roosevelt visited Roanoke Island on August 18, 1937— the 350th anniversary of Virginia Dare’s birth and a little more than a month after the July 4th premiere of Green’s drama. Prior to the performance of The Lost Colony, the President delivered an address.

Until recent years history was taught as a series of facts and dates. Today we are beginning to look more closely into the events which preceded those great social and economic and political changes which have deeply affected the known history of the world.

For example, most of us older people learned of Columbus’ voyages and how America came to be named—and we jumped from there in our North American history to the founding of Jamestown and of Plymouth—1492 to 1607—with mere passing reference to Roanoke and perhaps to the voyage of Verazzano.

It has always been a pet theory of mine that many other voyages of exploration and of trade took place in that century along our American shores. We know that during the same period the Spaniards established great colonies throughout the West Indies, at Panama and other points in Central America, and extended their cities, their religious institutions and even their universities to both the east and west coasts of South America. It is unbelievable that white men did not come scores of times to what is today the Atlantic Seaboard of the United States. Some day, perhaps, a closer search of the records of the seafaring towns of Britain and France and Flanders and Holland and Scandinavia will rediscover discoverers. Perhaps even it is not too much to hope that documents in the old country and excavations in the new may throw some further light, however dim, on the fate of the “Lost Colony” and Roanoke and Virginia Dare.

If we are to understand the full significance of the early explorations and the early settlements, if we are to understand the kind of world upon which Virginia Dare opened her eyes on that far-away August day in 1587, we must ask why Western Europe came to the New World.

It was in part because the era was an era of restless action. Under the Renaissance men experienced great awakenings; they were fired with restless energy to burst the narrow bounds of the medieval conception of the Universe, to fare forth on voyages of exploration and conquest.

Many of those who sailed in immense discomfort, in tiny ships, across the Atlantic, were adventurers, some of them seeking riches, some seeking fame, some impelled by the mere spirit of unrest. But most of the people who came in the early days to America—the men, the women and the children- came hither seeking something very different, seeking an opportunity which they could not find in their homes of the old world.

We hear of the gentlemen of title, who, on occasion, came to the Colonies, and we hear of the gentlemen of wealth who helped to fit out the expeditions. But it is a simple fact which cannot too often be stressed that an overwhelming majority of those who came to the Colonies from England and Scotland and Ireland and Wales and France and Holland and Sweden belonged to what our British cousins would, even today, call “the lower middle classes.” The opportunity they sought was something they did not have at home—opportunity freely to exercise their own chosen form of religion, opportunity to get into an environment where there were no classes, opportunity to escape from a system which still contained most of the elements of Feudalism.

This is said not in derogation of those pioneers. It is rather in praise of them. They had the courage, physically and mentally, by deed and word, to seek better things, to try to capture ideals and hopes forbidden to them by the laws and rulers of their own home lands.

It is well, too, that we bear in mind that in all the pioneer ‘settlements democracy, and not feudalism, was the rule. The men had to take their turn standing guard at the stockade raised against the Indians. The women had to take their turn husking corn stored for the winter supply of the community. In other words, they were all working for the life and success of the community. Rules of conduct had to be established to keep private greed or personal misconduct in check. I fear very much that if certain modern Americans, who protest loudly their devotion to American ideals, were suddenly to be given a comprehensive view of the earliest American colonists and their methods of life and government, they would promptly label them socialists. They would forget that in these pioneer settlements were all the germs of the later American Constitution.

It is well, too, that we bear in mind that in all the pioneer ‘settlements democracy, and not feudalism, was the rule. The men had to take their turn standing guard at the stockade raised against the Indians. The women had to take their turn husking corn stored for the winter supply of the community. In other words, they were all working for the life and success of the community. Rules of conduct had to be established to keep private greed or personal misconduct in check. I fear very much that if certain modern Americans, who protest loudly their devotion to American ideals, were suddenly to be given a comprehensive view of the earliest American colonists and their methods of life and government, they would promptly label them socialists. They would forget that in these pioneer settlements were all the germs of the later American Constitution.

They would forget, too, that throughout the days that intervened between Roanoke and Jamestown and Plymouth, and the time of the American Revolution itself, practical democracy was carried on in the lives of the inhabitants of nearly every community in the Thirteen Colonies. It is true that as commerce developed in the seaboard cities, and as a few great landed estates were set up here and there, a school of thought parallel with the same school of thought in England made great headway.

It was this policy which came into the open in the Constitutional Convention of 1787; for in that Convention there were some who wanted a King, there were some who wanted to create titles, and there were many, like Alexander Hamilton, who sincerely believed that suffrage and the right to hold office should be confined to persons of property and persons of education. We know, however, that although this school persisted, with the assistance of the newspapers of the day, during the first three National Administrations, it was eliminated for many years at least under the leadership of President Thomas Jefferson and his successors. His was the first great battle for the preservation of democracy. His was the first great victory for American democracy.

In the half century that followed there was constant war between those who, like Andrew Jackson, believed in a democracy conducted by and for a complete cross-section of the population, and those who, like the Directors of the Bank of the United States and their friends in the United States Senate, believed in the conduct of government by a self-perpetuating group at the top of the ladder. That this was the clear line of demarcation-the fundamental difference of opinion in regard to American institutions- is proved by an amazingly interesting letter which Lord Macaulay wrote in 1857 to an American friend.

This friend of his had written a book about Thomas Jefferson. Macaulay said “You are surprised to learn that I have not a high opinion of Mr. Jefferson and I am surprised at your surprise. I am certain that I never wrote a line and that I have never . . . uttered a word indicating an opinion that the supreme authority in a state ought to be entrusted to the majority of citizens told by the head; in other words, to the poorest and most ignorant part of society.”

Macaulay, in other words, was opposed to what we call “popular government.” He went on to say, “I have long been convinced that institutions purely democratic must, sooner or later, destroy liberty, or civilization, or both.”

Then, speaking of England, he said; “I have not the smallest doubt that, if we had a purely democratic government here, the effect would be the same. . . . You may think that your country (speaking of America) enjoys an exception from these evils. . . . I am of a very different opinion. Your fate I believe to be certain, though it is deferred by a physical cause. As long as you have a boundless extent of fertile and unoccupied land, your laboring population will be far more at ease than the laboring population of the old world, and while that is the case, the Jeffersonian polity may continue to exist without causing any fatal calamity. But the time will come when New England will be as thickly peopled as Old England. Wages will be as low and will fluctuate as much with you as with us. You will have your Manchesters and Birminghams, and in those Manchesters and Birminghams hundreds of thousands of artisans will assuredly be sometimes out of work. Then your institutions will be fairly brought to the test. Distress everywhere makes the laborer mutinous and discontented and inclines him to listen with eagerness to agitators who tell him that it is a monstrous iniquity that one man should have a million while another cannot get a full meal.” And then Macaulay goes on to tell his American friend how they’ handled such situations in England. He says “In bad years there is plenty of grumbling here and sometimes a little rioting, but it matters little. For here the sufferers are not the rulers. The supreme power is in the hands of a class, numerous indeed, but select . . . an educated class . . . a class which is, and knows itself to be, deeply interested in the security of property and the maintenance of order. Accordingly the malcontents are firmly yet gently restrained. The bad time is got over without robbing the wealthy to relieve the indigent. The springs of national prosperity soon begin to flow again . . . and all is tranquility and cheerfulness.”

Then, speaking of England, he said; “I have not the smallest doubt that, if we had a purely democratic government here, the effect would be the same. . . . You may think that your country (speaking of America) enjoys an exception from these evils. . . . I am of a very different opinion. Your fate I believe to be certain, though it is deferred by a physical cause. As long as you have a boundless extent of fertile and unoccupied land, your laboring population will be far more at ease than the laboring population of the old world, and while that is the case, the Jeffersonian polity may continue to exist without causing any fatal calamity. But the time will come when New England will be as thickly peopled as Old England. Wages will be as low and will fluctuate as much with you as with us. You will have your Manchesters and Birminghams, and in those Manchesters and Birminghams hundreds of thousands of artisans will assuredly be sometimes out of work. Then your institutions will be fairly brought to the test. Distress everywhere makes the laborer mutinous and discontented and inclines him to listen with eagerness to agitators who tell him that it is a monstrous iniquity that one man should have a million while another cannot get a full meal.” And then Macaulay goes on to tell his American friend how they’ handled such situations in England. He says “In bad years there is plenty of grumbling here and sometimes a little rioting, but it matters little. For here the sufferers are not the rulers. The supreme power is in the hands of a class, numerous indeed, but select . . . an educated class . . . a class which is, and knows itself to be, deeply interested in the security of property and the maintenance of order. Accordingly the malcontents are firmly yet gently restrained. The bad time is got over without robbing the wealthy to relieve the indigent. The springs of national prosperity soon begin to flow again . . . and all is tranquility and cheerfulness.”

Almost, me thinks, I am reading not from Macaulay but from a resolution of the United States Chamber of Commerce, the Liberty League, the National Association of Manufacturers or the editorials written at the behest of some well-known newspaper proprietors in 1936 and 1937.

Like these gentlemen of 1937, Macaulay in 1857 painted this gloomy picture of the future of the United States: “I cannot help foreboding the worst. It is quite plain that your government will never be able to restrain a distressed and discontented majority. . . . The day will come when . . . a multitude of people, none of whom has had more than half a breakfast or expects to have more than half a dinner, will choose a legislature . . . On one side is a statesman preaching patience, respect for vested rights . . . On the other is a demagogue ranting about the tyranny of capitalists . . . and asking why anybody should be permitted to drink champagne and to ride in a carriage while thousands of honest folks are in want of necessaries. . . . I seriously apprehend that you will, in some such season of adversity . . . do things which will prevent prosperity from returning; that you will act like people who should in a year of scarcity devour all the seed corn and thus make the next year a year, not of scarcity but of absolute famine. . . . There is nothing to stop you. Your constitution is all sail and no anchor. . . . Either some Caesar or Napoleon will seize the reins of government with a strong hand, or your Republic will be . . . laid waste by Barbarians in the twentieth century as the Roman Empire was in the fifth.”

That, my friends, with all due respect to Lord Macaulay, is an excellent representation of the cries of alarm which rise today from the throats of American Lord Macaulays. They tell you that America drifts toward the Scylla of dictatorship on the one hand, or the Charybdis of anarchy on the other. Their anchor for the salvation of the Ship of State is Macaulay’s anchor: “Supreme power . . . in the hands of a class, numerous indeed, but select; of an educated class, of a class which is, and knows itself to be, deeply interested in the security of property and the maintenance of order.”

Mine is a different anchor. They do not believe in democracy—I do. My anchor is democracy—and more democracy. And, my friends, I am of the firm belief that the Nation, by an overwhelming majority, supports my opposition to the vesting of supreme power in the hands of any class, numerous but select.

It is of interest to read the whole of Macaulay’s letter with care—for I find in it no reference to the improving of the living conditions of the poor, to the encouragement of better homes or greater wages, or steadier work. I find no reference to the averting of panics, no words for the encouragement of the farmer-nothing at all, in fact, except the suggestion that “malcontents are firmly but gently restrained” . . . in the interest of the “security of property and the maintenance of order.”

I am just as strongly in favor of the security of property and the maintenance of order as Lord Macaulay, or as the American Lord Macaulays who thunder today. And in this the American people are with me, too. But we cannot go along with the Tory insistence that salvation lies in the vesting of power in the hands of a select class, and that if America does not come to that system,’ America will perish.

Macaulay condemned the American scheme of government ‘based on popular majority. In this country eighty years later his successors do not yet dare openly to condemn the American form of government by popular majority. They profess adherence to the form, but, at the same time, their every act shows their opposition to the very fundamentals of democracy. They love to intone praise of liberty, to mouth phrases about the sanctity of our Constitution—but in their hearts they distrust majority rule because an enlightened majority will not tolerate the abuses which a privileged minority would seek to foist upon the people as a whole.

Since the determination of many who compose this minority is to substitute their will for that of the majority, would it not be more honest for them, instead of using the Constitution as a cloak to hide their real designs, to come out frankly and say: “We agree with Macaulay that the American form of government will lead to disaster and therefore we seek a change in the American form of government as laid down by the Founding Fathers?”

They seek to substitute their own will for that of the majority, for they would serve their own interest above the general welfare. They reject the principle of the greater good for the greater number, which is the cornerstone of democratic government.

Under democratic government the poorest are no longer necessarily the most ignorant part of society. I agree with the saying of one of our famous statesmen who devoted himself to the principle of majority rule: “I respect the aristocracy of learning; I deplore the plutocracy of wealth; but thank God for the democracy of the heart.”

I seek no change in the form of American government. Majority rule must be preserved as the safeguard of both liberty and civilization.

Under it property can be secure; under it abuses can end; under it order can be maintained—and all of this for the simple, cogent reason that to the average of our citizenship can be brought a life of greater opportunity, of greater security, of greater happiness.

Those worthy hopes led the father and mother of Virginia Dare and the fathers and mothers from many nations through many centuries to seek new life in the New World. Pioneering it was called in the olden days; pioneering it still is- pioneering for the preservation of our fundamental institutions against the ceaseless attack of those who have no faith in democracy. Fortitude and courage on our part succeed the fortitude and courage of those who planted a colony on this Island in the days of good Queen Bess.

-President Franklin D. Roosevelt

August 18, 1937

Roanoke Island, NC